τοῖς δὲ προφήταις ἐπιτρέπετε εὐχαριστεῖν ὅσα θέλουσιν. Let the prophets make the Thanksgiving as they wish.

This, from some of the earliest instructions on how Christians might perform their services, is from a section perhaps best known for its prayers about gathered wheat and knowledge, but contains this line: those with the gift should not feel the need to keep to formulae but can ad lib. the prayers at the heart of the liturgy. It’s a far cry from the tomes we lug around in Catholic services.

However, those tomes are up for further rewriting.

What follows is a weaving together of various statements without (I hope) my intruding too much: The news last week was that the Vatican (more precisely the Dicastery for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments) has confirmed the approval by the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales for the new Lectionary. Based on the lectionary already in use in India and using a “revised” (see below) psalter from Conception Abbey in the US it aims to “ensure that the Word of the Lord reaches God’s holy people without alloy” – meaning… “avoiding paraphrase whilst maintaining the poetry and rhythm of the psalter.” https://www.cbcew.org.uk/new-lectionary-to-be-launched-in-england-and-wales-for-advent-2024/

In 2008 a revision of the text was undertaken by the monks of Conception Abbey, Missouri. It sought to bring the latest scholarly understanding of the text and to review the text where the English was essentially a paraphrase of the Hebrew. This text was approved by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and further revision has been prepared and approved has received the confirmatio of the Holy See. This text is now owned by USCCB who have renamed it Abbey Psalms and Canticles both in recognition of the work of Conception Abbey and also so that there was clarity about the edition being used. This text will be used in the Lectionary and in subsequent liturgical books, such as the Liturgy of the Hours.

In response to the question Will the text be mandatory?

It is normal practice in the Roman Rite that there is only a single edition of a liturgical text in use in a particular territory. So in the same way as only the third edition of the Roman Missal (2010) may be used in the celebration of Mass (in the Ordinary Form); the same will be true for the Lectionary.

https://www.cbcew.org.uk/new-lectionary-for-england-and-wales/

So a while back this move was approved, the texts set up and a number of music writers (in the US only?) involved in creating settings for the psalms. A number of sources have said these are a revision of the Grail translation where the texts in use were “paraphrases.” It’s hard to give sufficient weight to this argument without specific examples, but certainly there are points at which the current translations of the psalms do not always keep as closely as one might expect to earlier texts and translations, but equally the task of a translator of poetry cannot easily be dismissed as “paraphrasing.” I know that any reform might want to start by overegging the case for the need to reform, but I think we also have to admit that this is not really a simple revision of the Grail translation per se, but uses the Grail psalms as a basis on which to build a different (and maybe simply more flowery) version of the psalm texts. Today, for example, the Feast of the Transfiguration, has the new translation of the Response in the Psalm at Mass as

The Lord reigns, the most high over all the earth

while the current response is:

The Lord is King, Most High above all the earth

and the two versions of “verse 1” are

The Lord reigns; let the earth rejoice:

Let the many islands be glad.

Cloud and thick darkness are round about him;

Righteousness and justice are the foundation of his throne.

compared with

The Lord is King, let earth rejoice,

Let all the coastlands be glad.

Cloud and darkness are his raiment,

His throne, justice and right.

They are alike enough to see they are clearly the same text – but not unlike enough to seem (to me) to need tinkering with.

Tinkering. Ah, a cat is out of a liturgical bag here, I think. This seems to me not so much about accuracy – about treaures without alloy, text without paraphrase – as an intention to bring the often rather stiff language of the new translation of the Missal (and the Breviary, see below) further into the usage of the liturgy.

It has received its confirmatio from those with authority; like the translation of the Mass we are – depending on where you sit with this – overjoyed at the change of tone, or stuck with it.

It will, however, require more than just a change to the Lectionary.

People who bought the (rather unwieldy) CTS Missal might feel they were sold something with a sell-by date on. The same might be true for those communities, choirs, &c who bought hymnals with new Mass settings (and annoyingly, new numberings and occasional content changes). If “there is only a single edition of a liturgical text,”(see above) then the music for responses and alleluia verses will also need revision; the music being produced in US certainly suggests this has been an opportunity for new music to be written, just as it was with the new translation of the Missal itself – and after this will come the Breviary. No wonder this vast project has not as yet an estimated date for publication (bcew.org.uk/new-lectionary-for-england-and-wales/). In the run up to the beginning of the new translation of the Lectionary – the next step in the longer project – perhaps we need to be thinking about some actions:

- Given that the new text is not optional, music that is simple and enjoyable to sing by congregations and communities needs to be trialled – not just put into new editions of hymn books;

- Some new editions of hymn books need complete revision; Laudate, for example, with its liturgical and thematic ordering, was always rather a trial to navigate, but became much more so with the rather random replacement of some bits and pieces; the two editions are uncomfortable to use together;

- A provisional lectionary therefore needs to be released soon;

- This is an opportunity for liturgists (at parish, diocesan, even in media levels: a broad hint to self here) to work with choirs, bands, organists so that the responsorial psalm becomes or is reinforced in its position as what it was intended to be: part of the proclaimation of the Word of God. The time for study groups to look at, to learn to be familiar with the psalms is now, or at least from this Advent, so that next Advent (2024) feels less of the kind of shock that went through congregations when the new Missal was imposed. And I have a cunning plan for singing the psalms…

The responses to the psalms that have been used since the introduction of the Responsorial Psalm have been many and of varying complexity. I do worry sometimes that musicians choosing the melodies sometimes do not have a range of settings that are congregation-friendly. This has to be – as with Mass settings – something publishers take into account as much as singers. The new translations seem to me to have deliberately taken out the distinctive sprung rhythm that Joseph Gelineau developed. One way to develop our psalm singing is for psalm tones – the ones based in the traditonal Latin tones, or the ones from the style of Laurence Bevenot – also to be used in the response. It might make for a plainer “performance” (not sure I like this word in this context but never mind) but it would retain an element of singability. With the modulations coming at the end of the line, syllabic changes on the main, reciting note (“Cloud and thick darkness are round about him” instead of “Cloud and darkness are his raiment”) would not affect the singability.

So this is maybe just a long post simply to say “There is some work ahead of us.” Some of that work will be better enjoyed the more thoughtful it is; the better the preparation (and the more help we have to develop our own music or our own choices within new music produced) the easier it will be to be thoughtful.

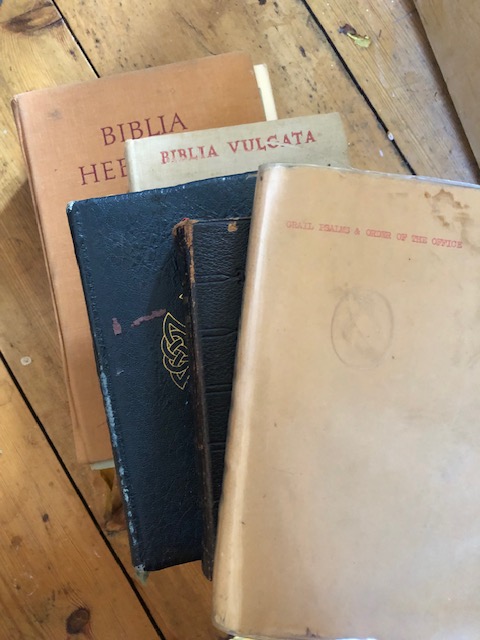

And the image above? Well the two bottom books are obvious, although I really struggle – I mean really really struggle – with the Hebrew – and the next one up is Vol 1 of my Breviary, which I bought in the 70s. There’s also a volume of the pre-reform Monastic Breviary. And the top one? The predecessor to the Breviary was called Prayer of the Church (which some unkindly called “Plastic Prayer” because of its squeaky cover and plastic pockets for supplementary material) and before that, this now incredibly battered, unedited copy of the the Grail Psalter, which I made myself while I saved up. Will the new Breviary be something I buy and learn to love? Will I just go online for it all?