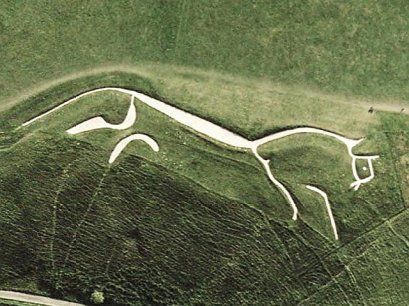

Side by side, Lubrin and Cradoc stepped onto the bare white chalk of the mare’s breast. A low, rhythmic murmur rose from the gathered priests, and was taken up by the crowd, rising louder and louder, becoming prayer and triumph-song in one. The mare’s arched neck was like a royal road, and Lubrin walked up it like a king going to his king-making. He came to the strange, half-falcon head, and it seemed to him that the proudly-open eye stared back at the sun and moon and circling stars and the winds of all the world….

When Lubrin Dhu, the protagonist of Rosemary Sutcliff’s book Sun Horse Moon Horse finally steps out onto the chalk figure he has envisaged, the world she has created – with its beliefs and lives, the emnities and loyalties – is wholly believable. She does the same when Eugenus speaks into the darkening world at the end of The Lantern Bearers, as I discussed earlier. Such is her power as a writer.

She draws on her understanding of place, of what we might tentatively call “real places” – such as what we would now call Uffington Castle, or the cities and oppida of failing Roman Britain or the (earlier) security of Calleva Atrebatum or the Viking settlements in the eleventh century – to create worlds in which believable characters meet believable crises. She creates – to refer again to a previous blog post – a World We Feel At Home In.

But this world-building is not without its perils; it sits very often beyond the immediately knowable (or guessable) in a history of documentary fragments and archeological investigation. In this respect it is like fantasy; Alan Garner in, say, Thursbitch, and Lucy Boston in the Green Knowe books explore its interplay between a modern world and a world of the past; Peter Dickinson’s The Kin looks at making an origin-myth for humanity without the modern reference, although the modern reader is never far away, and T H White’s Once and Future King uses the myth of Arthur as a lens for his own world. “Pure” (I don’t think I like that word) historical fiction like Sutcliff or Clive King’s The Twenty-Two Letters or Hilary McKay’s The Skylarks’ War attempt to step away from fantasy and present a world we can find wholly beliveable. We can visit some of the sites of the stories as they are today; we can look to see what evidence there is for the way the authors depict it, but our contract with the author and the text is that we should believe that this is how it was.

And then comes a book like this. David Miles – whose credentials for the work are not in doubt – creates in his book The Land of the White Horse (2019: Thames and Hudson) an exciting account of the archaeology – and more – of the Uffington site where Sutcliff places her action for Sun Horse Moon Horse.  His book looks at the research he and others have done, the growth of understanding of the White Horse and its surroundings, and asks the biggest question of all, about the impetus for keeping this hill figure “alive.” Miles begins his section (pp166- 7) on Sun Horse Moon Horse stressing the formative influence of Trease, Treece, Syme, Serrallier and Sutcliff in his own childhood, but does admit that she tells the story of the creation of the White Horse “with a mythical simplicity.” However, he has to be plain about his findings: “The premise of the story is highly unlikely… the story is historically dubious.”

His book looks at the research he and others have done, the growth of understanding of the White Horse and its surroundings, and asks the biggest question of all, about the impetus for keeping this hill figure “alive.” Miles begins his section (pp166- 7) on Sun Horse Moon Horse stressing the formative influence of Trease, Treece, Syme, Serrallier and Sutcliff in his own childhood, but does admit that she tells the story of the creation of the White Horse “with a mythical simplicity.” However, he has to be plain about his findings: “The premise of the story is highly unlikely… the story is historically dubious.”

Does this invalidate the story? No, but it changes the focus. David Rudd in Grenby and Reynolds’ Children’s Literature Studies: A Research Handbook suggests that

…all histories are provisional, always open to rewriting…

and while Rudd (and Grenby) are mostly discussing historical research into (or using) children’s literature, many of their insights can also be seen as touching on books which are set in the past. If stories from the past help the researcher understand the historical context in which they were written (Rudd uses Wind in the Willows extensively), then we might see stories about the past (especially the distant or hard-to-access past: Kathleen Fidler’s Boy with the Bronze Axe, Cynthia Harnett’s Writing on the Hearth, to cite two less currently well read text) as somehow part of the writing of the history. But they are particularly “open to rewriting” when our understanding of the time period is challenged. Will I be able to read Mantel’s Mirror and the Light with the same delight now I have read MacCulloch?

Sutcliff’s vision of what we now term “Uffington Castle” as a place people lived has been overturned; a different book would have to be made of a Late Bronze Age gathering space or sacred site. Perhaps the ending would not have been so different; perhaps the warring between tribes or the self-sacrifice of the artist would have been the same. Perhaps what matters is not the accidentals of context but the matter of the story, and that the rewriting that archaeology and other scholarship do not diminish the power of the fiction, the shape of the story, the characters and the outcome. If Sun Horse Moon Horse is now more fantasy than historical account, does the difference matter?

The difference lies between a work of fiction from the 1970s and a work of scholarship from the new millennium. Miles clearly loves much of the thinking behind Rosemary Sutcliff’s vision:

Sutcliff describes beautifully the motivation of the artist and the practical way he creates the large White Horse images by scaling up a small drawing… She evokes the flight of the swallows and how they convey the image of speed and eleganc to the artist. She sees the White Horse image as an abstract masterpiece, capturing the essence of the Sky horse, galloping at speed across the heavens.

and he is happy to see the archaeology of a sun cult as having these elements, too, as he cites the horse in the Vix torc and the Trundholm sun chariot. For her time Sutcliff knew a lot about this, and if for Miles as an archaeologist Sutcliff’s sources do not always bear too close an inspection (David Miles is acidly terse when he describes one of her principal sources as “an avid promoter of dowsing”) she is clearly on the right lines in many ways. Maria Tatar cites Disney as saying “We just try to make a good picture,” and (if I can twist the saying a little) the view of the harebell growing where Lubrin lies on the White Horse is a very good picture indeed.