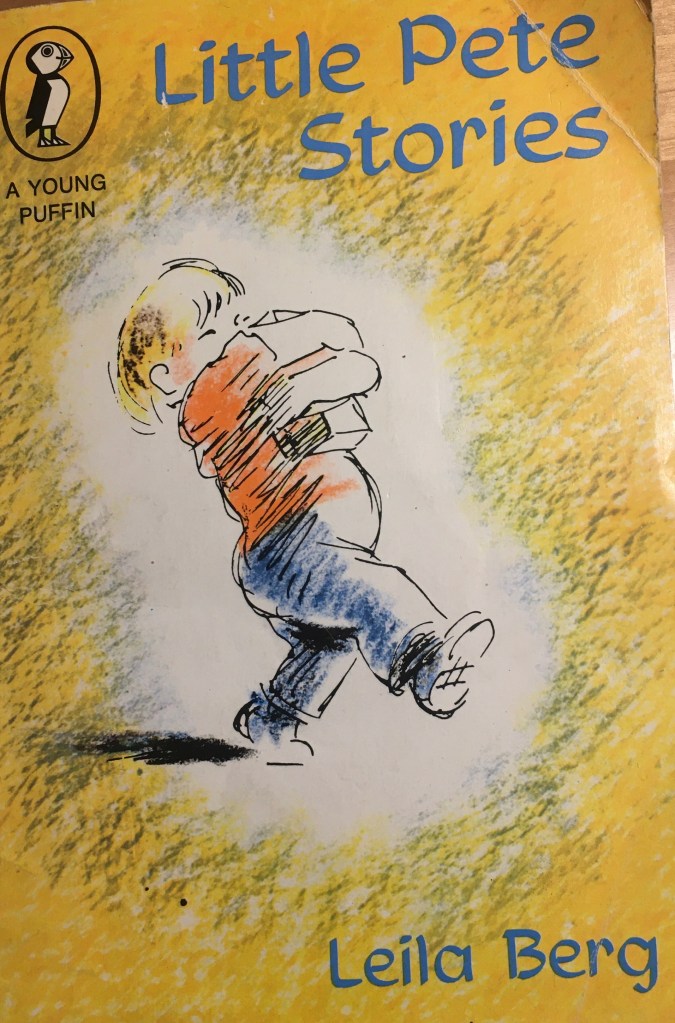

It is a sort of running gag with me that my Goodreads account ought to have a shelf on it marked “Books Mat Showed Me That Made Me Cry.” Mat has the great gift of seeing a book through and through, welcoming the shadows as well as the sunshine: often he suggests I read a book so moving, so poignant, that when I have finished I have a lump in my throat. It is good, therefore, to move from these wondrous books that wrench the heart, to a very old but certainly gold collection: the Little Pete Stories by Leila Berg. Mat, thank you for these, and for the joy they have brought as I’ve shared them with my granddaughter.

When Pete is disturbed playing at not treading in the cracks in the pavement he rails at the lady in the Bath Chair who has interrupted him:

“You’ve turned me into an elephant!” he cried.

“You don’t look like an elephant,” said the lady who sat in the chair.

“You’ve turned me into an elephant!” Pete shouted. “You’ve made me tread on hundred and millions of lines and now I’m an elephant and I wasn’t going to be an elephant till I got to the top of the hill, so I could run all the way down!”

Leila Berg “Pete and the Letter” (Little Pete Stories ch 7)

There is a knowing wink to the reader here: we all know he isn’t a elephant, any more than his personification of his shadow (which occurs throughout) is someting that is actually “true,” and we also know that Pete understands that he isn’t an elephant, but that he is expressing his dismay at an imaginative game being interrupted. The rational adults who encounter Pete’s anger and impatience usually get round it in some way, and very often this is by their involving him in something – such as posting a letter, the subject of this story – and this strikes me as crucial in Berg’s vision of childhood. Pete is not to be told “don’t shout:” it doesn’t work, although practically every adult tries it; Pete, they discover, is best distracted and redirected, but in a very specific way, in that the adults find ways of engaging him in meaningful activity.

The child’s despair is all encompassing – because he does not know gradations, he feels either in darkest hell or gloriously happy…

As Bettleheim puts it, describing the role of the Happy Ever After of becoming a King or Queen in the finale of a fairy tale:

There is no purpose to being the king or queen of this kingdom other than being the ruler rather than being ruled. To have become a king or queen at the conclusion of the story symbolizes a state of true independence in which the hero feels… secure, satisfied and happy…

Bruno Bettleheim ‘Transcending Infancy with the Help of Fantasy in “The Uses of Enchantment”

Pete is given agency from the start – Berg allows him to express his frustration when he is crossed – and in the denouement of his narratives of crisis, and that leads to the stories’ punchline invariably being about that day being “good.”

He has quite a lot of agency. He is out on his trike on his own, going to the shops, watching builders: this neighbourhood is full of interesting things for a small boy to do. He even gets a lift to buy a notepad from a man on whose car he has been writing with a stick, although in the version I have (1971) he asks his mum, who does check and allows him. The stories thus stand as testament to a childhood I think we rarely see in the UK these days – at least, one that is not recorded. This is the same world as the US childhood depicted in The Sign on Rosie’s Door (from 1′ on in this clip, in the 80th birthday tribute to Maurice Sendak), although Sendak’s is much more social. Pete’s world was described maybe ten years before I experienced it, and the world was changing. I felt sad having to explain this to a seven-year-old when I started on sharing these stories, in much the same way as a discussion of lifts from strangers feels like a necessary introduction to The Elephant and the Bad Baby (lots more to say about that story!).

Pete explores with confidence and copes with the events that thwart his plans. He reacts with an unregulated anger or impatience – and in some ways the best thing about this is how the narrator allows this expression of anger. He has the much-pined-for freedom that is deep in the narrative of nostalgia: in some ways his physical and emotional freedom is the epitome of this version of childhood freedom. It is one I recognise from my own childhood: my own tricycle when I was three or four, the casual interactions with people I knew or at least who knew me: Harrogate; Charlton Marshall and Blandford Forum in Dorset, even before the freedoms of bike-friendly Harlow in Essex when I was eight (two-wheeler by now! – I still have the scars)…

So in Leila Berg’s 1950s we have a small person – just beginning to write (and that and the trike suggest he is four, but I’m happy to be corrected) out and about with adults keeping a regulatory eye but not systematically organised on his explorations. Pete is a lone hero with odd cats and dogs and sticks – and of course his shadow – for company. The interactions with adults are gradually – very gradually – teaching Pete about the world around him. For me the most touching is Pete’s interaction with a builder. It starts with Pete being cross about how people build – up, he thinks, with walls, not down into foundations. But the builder gives him some time:

“Well,” said the man, “if you’ll listen very carefully – and quietly – and lave my spade alone – I’ll explain it to you.” And he wiped his hands on his trousers, for there were feeling rather sore and sticky.

And because Pete could see that what the man was going to tell him would be the truth, he stopped being angry and listened.

Pete and the Whistle.

The man was going to tell him the truth. That is one of the most insightful lines in the book: and if we expect the dance of adult and child regulation to be success, it is at the heart of our parenting and pedagogy.

In The Sign on Rosie’s Door the regulation more or less comes from the group of children; the flock keeps the flock safe, although it is interesting that joining a group and leaving it is very casual. There is freedom here too, freedom for slightly older children, freedom of a different order from Little Pete – freedom from the ties of the adult. The entertaining autobiography of David Benjamin has similar insights, reflecting on Wisconsin (of maybe a slightly older child) from a similar period:

Kids are instinctively feral. Unleash them from school and church and home, as every kid was invariably set loose every summer in the Little-League-less Fifties, and kids will hunt down whatever wild game crawls into their territory.

The summer hunt is an ecstasy of freedom. Suddenly, the last days of May, after a useless morning in class, school ends. The doors open and kids stumble, blinking, into the sun. We hear our first robin sing. We see our first forsythia. We breath chalkless, nunless, heathen air. We break into a run…

David Benjamin ‘Koscal’ in “The Life and Times of the Last Kid Picked.”

Kids would like to be feral, and yet as a parent I was (and as a grandparent am still) tempted to put limits on their natural wanderlust. I understand that as a toddler I frequently disappeared in 1950s Hong Kong on my trike, and in my later pre-teens I often hired a bicycle and rode off for an hour or two at a time, usually ending up at a comics stall engrossed in some DC comic or other. So Leila Berg’s storylines are perfectly comprehensible to me in a way they mightn’t be for a 21st century child.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know what you mean about how children move round their neighbourhoods – some work about ten years ago suggested a drastic loss of “play radius,” over the last fifty years. I don’t know if lockdown has changed this: my back-of-an-envelope observation is that more children are playing out in quieter streets, but whether this is so, or so for all children, or sustainable… well, I wouldn’t like to speculate. I’d like to suggest that our Gwyn has huge freedom – but that access to a wide range in effect cost his sister her life, and much as I loved a lot of my freedom to roam, it was also at the cost of more scraps and other misfortunes: we were free, maybe, but not invulnerable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder how much freedom Gwyn actually would’ve had in the 1980s context of the trilogy: his family’s hill farm obviously ranged quite a bit, and he regularly accessed his Nain’s and neighbours’ homes, but I’d imagine he’d normally be expected to do his fair share of work, especially as with the loss of Bethan there’d have been less support with livestock and daily tasks.

I can only go on our grandkids’ limitations during lockdown, cooped up at home or allowed out under strict supervision. And you’re right about our relative freedoms meaning greater physical risks: but I can’t remember which wise person wrote that we should stop saying ‘Take care!’ when our kids went out on their own, because that either led to them being over anxious or irritable; better to say ‘Take risks!’ because this gave them control and personal responsibility, and indicated trust that they would do the right thing.

LikeLike

I spotted this short fable I wrote for a creative writing exercise a few years ago which sort sums up what I was on about earlier:

https://wp.me/s4H9zI-bran

LikeLike