This (rather image-heavy) post is principally for ‘my’ undergraduates in Outdoor Learning and for the MA students in Children’s Literature through the ages. For this reason, although it jumps about a bit, it essentially is trying to cover ground they may (or let’s face it may very well not) find useful. Covering ground: metaphor already. At any rate the two modules each have their own concerns about the relationship between literature and place.

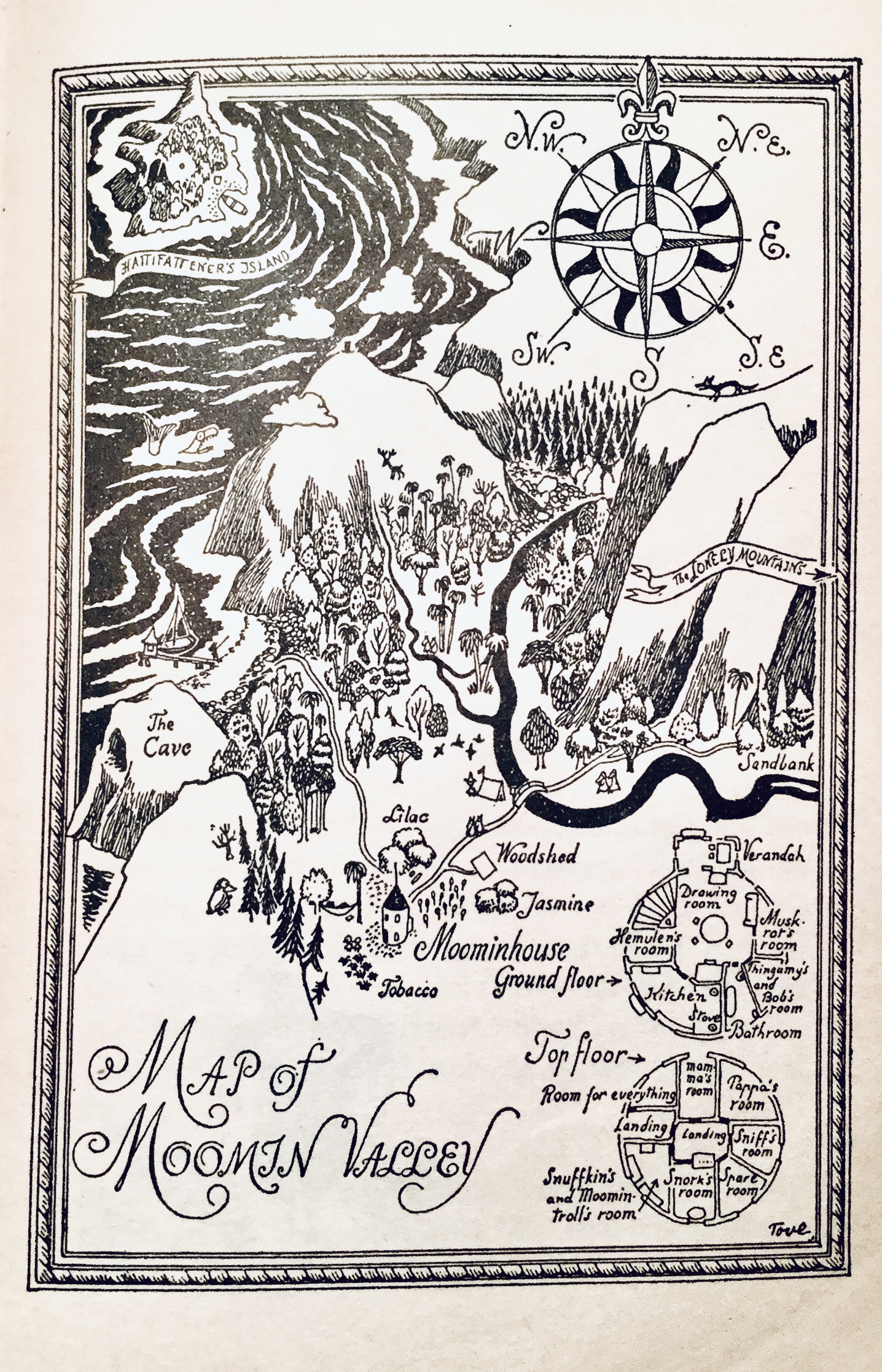

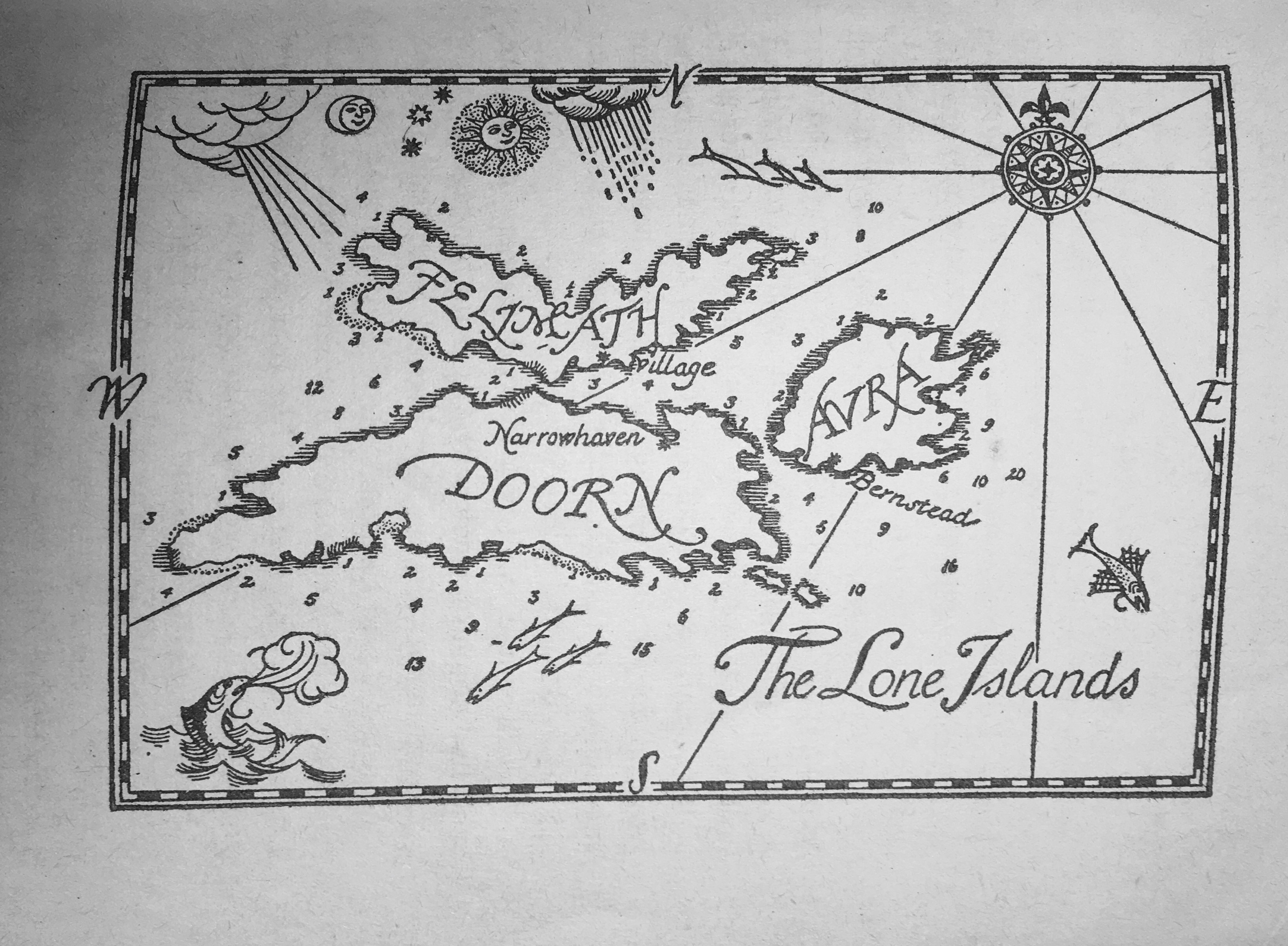

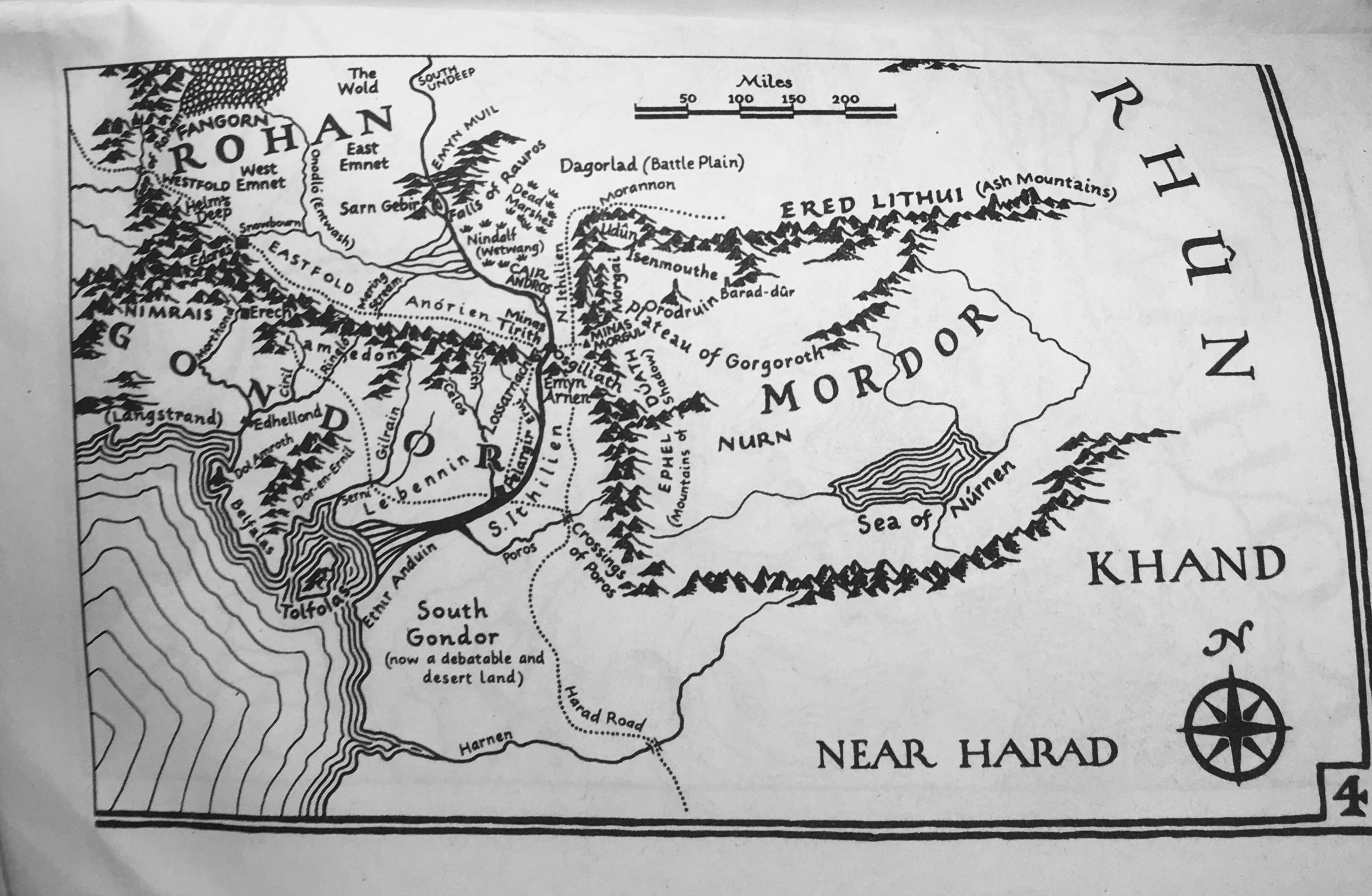

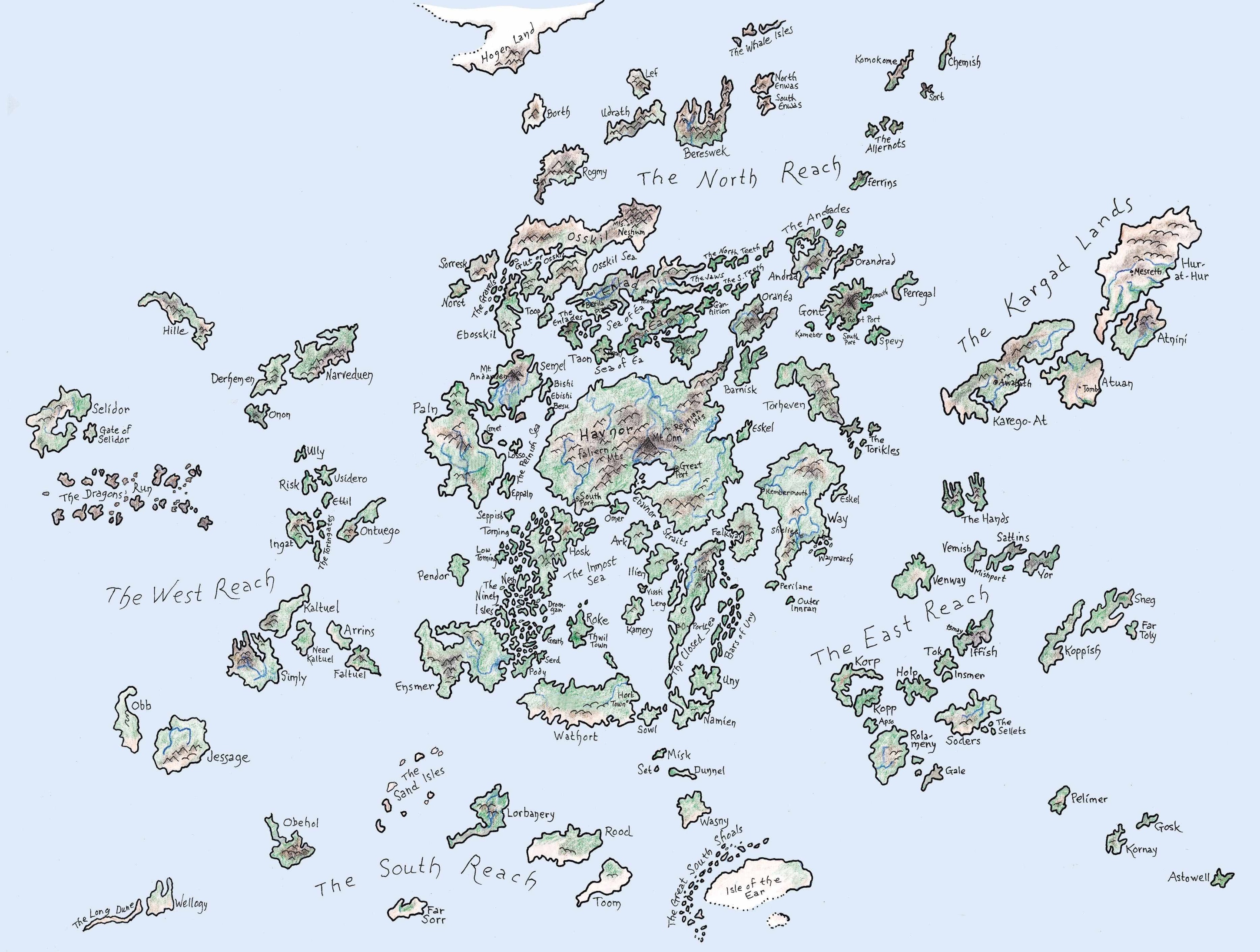

Perhaps I should start with a quick run-down of some maps I can lay my hands on easily: Lewis (Baynes), Tolkien and Le Guin, the sources being my Puffin Voyage of the Dawn Treader, my paperback of The Two Towers and (because the representation of Earthsea I have is over the gutter of an endpaper) Ursula K Le Guin’s Estate website. They are all of places in fantasy literature, but that’s just because I’m reading Le Guin at the moment; one of my favourites ends this post. Maybe, as Simon Schama invites us to see the ghostly outline of an old landscape beneath the superficial coverings of the contemporary (Landscape and memory, p16), the maps of fantasy worlds also invite us to look at our own world.

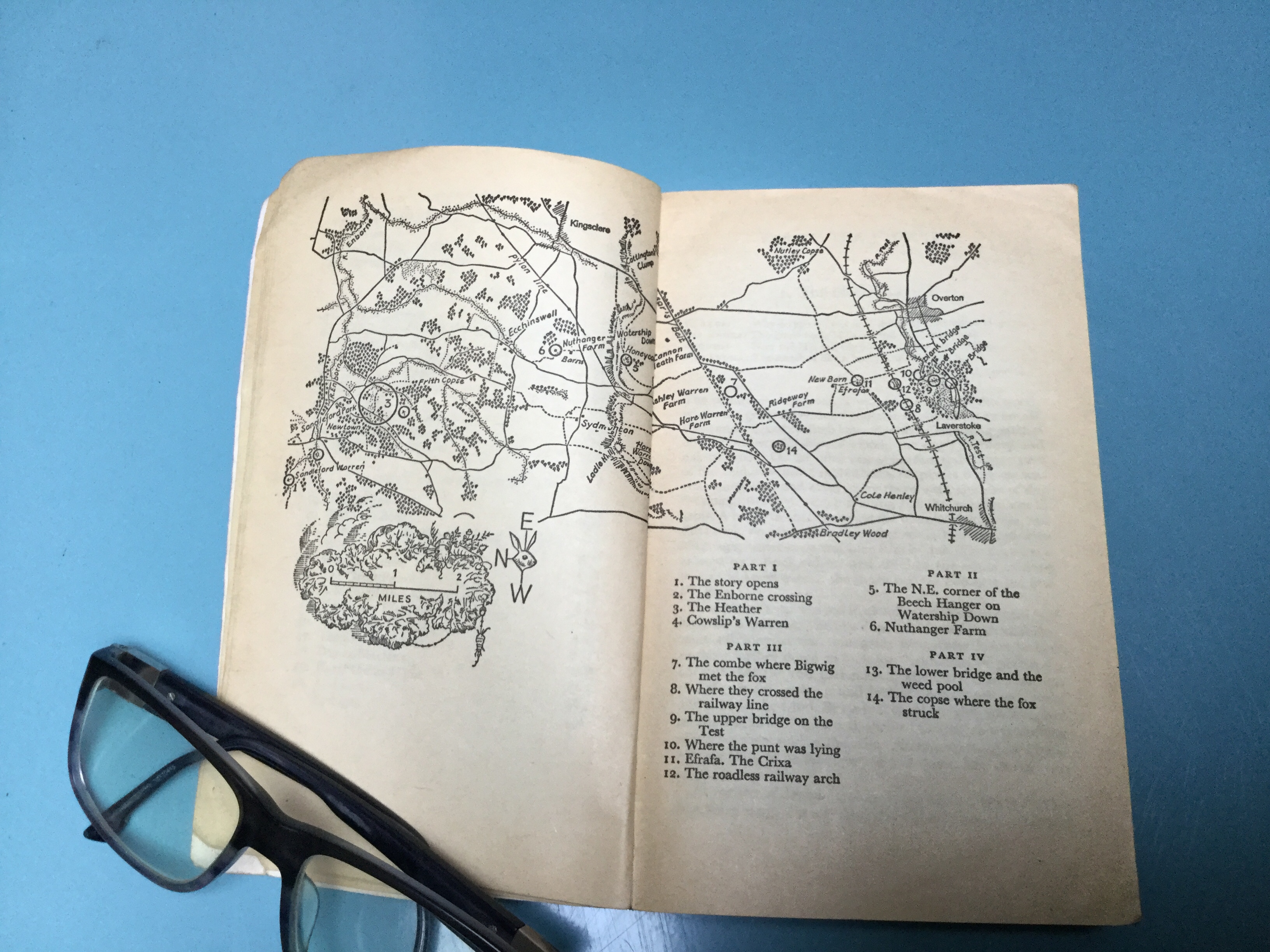

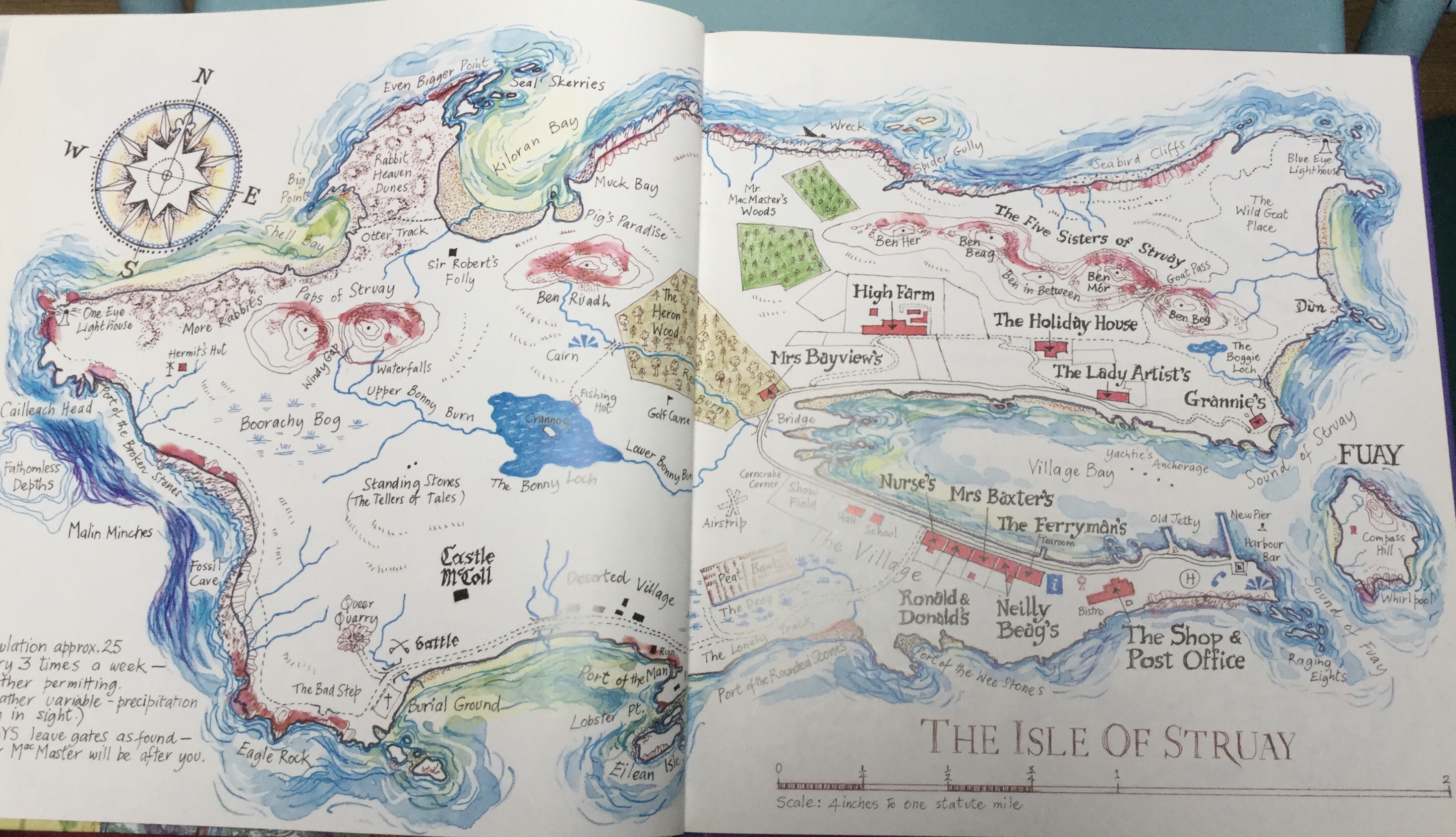

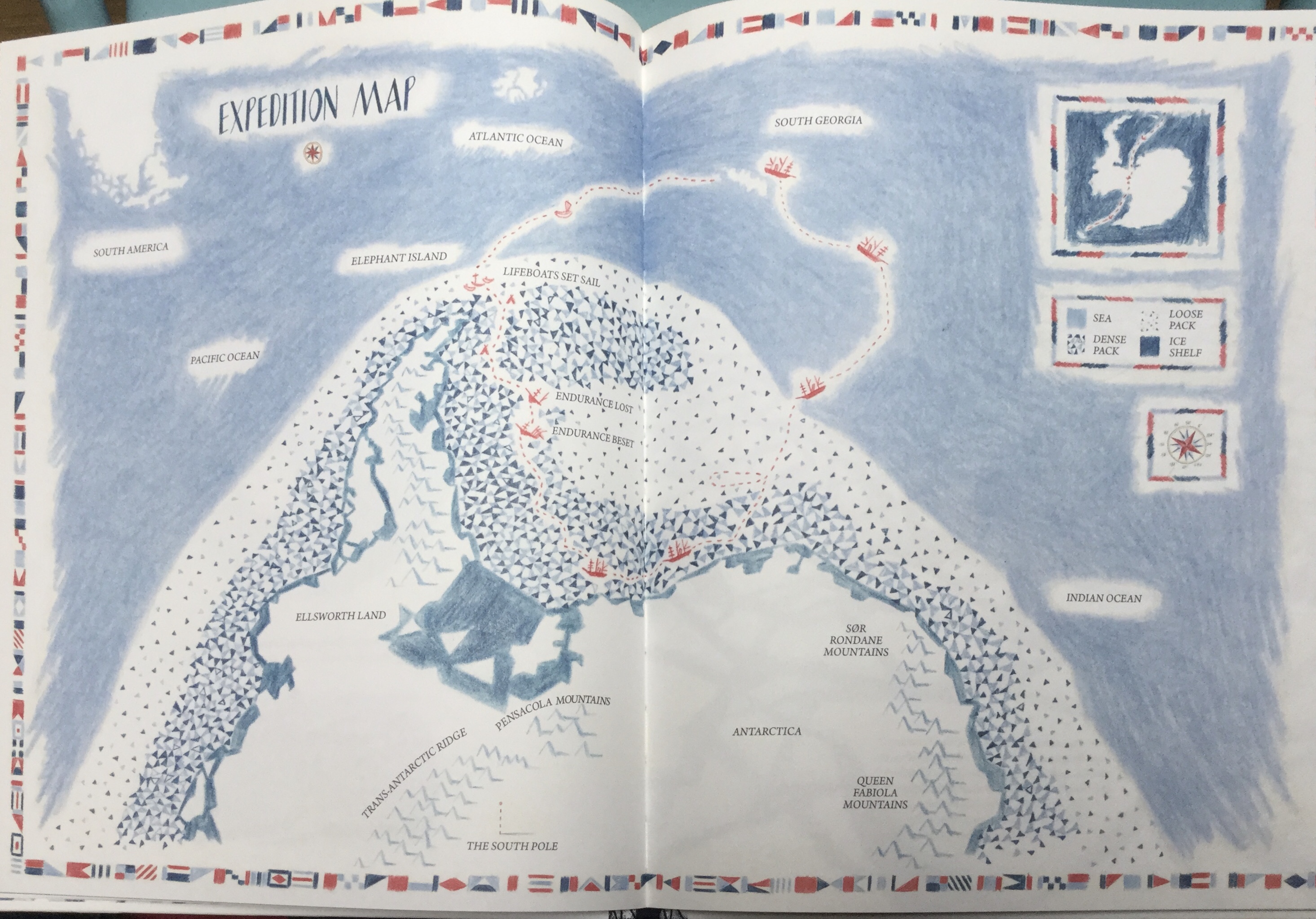

Maps have been discussed as an important part of the writing and reading processes for all sorts of authors – here is Tolkien’s famous dictum on the subject – but I want to think about what they do in a story. Sometimes, as in Watership Down they build a sense of reality – Watership Down being a good case, a story built around a real place; we might also consider the Antarctica of Shackleton’s expedition (another real place) or Katie Morag’s only-just-fictional home island of Struay. Thorin’s map in The Hobbit stands as a way of telling us about the lie of the land, gives Tolkien – through Gandalf and the dwarves – some reason for plot exposition as it is explained to Bilbo, and is the map they use to find a way into the Lonely Mountain. We might also recognise that the absence of a map – as in Garner’s Thursbitch (my comment on maps is here) or The Owl Service – sometimes has a hand in enhancing the mystery. But perhaps Garner is a digression.

Do what do maps do in stories? They are sometimes there to anchor the storytelling for the readers – to show us, if not Frodo, the way to Mordor; to show us, if not Hazel, a Kehaar’s-eye view of the Downs. They are also props in the story: Pauline Baynes’ map of the Lone Islands in Voyage of the Dawn Treader is a nautical map to roll out on a table. And beyond this are illustrations such as William Grill’s maps in Shackleton’s Journey, integral to the reader’s understanding of the routes and the perils along it.

Maps of a real or fictional place cannot replace entirely the narrator’s skill, any more than a writer can describe a landscape with the overlapping details of, say an OS map, without an exhaustive set of appendices or digressions. Ursual Le Guin’s own line is revealing:

Its use to me was practical. A navigator needs a chart. As my characters sailed about, I needed to know how far apart the islands lay…

and she poses herself the key questions for her conjuring Earthsea;

What island lay farthest to the west. Selidor. Look at Havnor: big enough that there might be people living inland who’d never seen the sea. What sort of magic did they really do in Paln? What about the big Kargish land of Hur-at-Hur, way out there as far east as Astowell and quite unknown to the Archipelgans – were there ever dragons there?

U K Le Guin “The Books of Earthsea:” Introduction

For le Guin the map provides the shelves on which the stories will grow, like in a greenhouse. We follow her about as she follows her characters. What is it like, this place?

But sometimes it is left to the critic to put flesh on the bones of landscape – for example Chris Lovegrove and his work on (among other lands and universes) Joan Aiken’s world of Willoughby Chase. This doesn’t let the writer off the hook of course, so when the rabbits come to what will be their stronghold in Watership Down the map (see above) gives way to the desciption:

Now with his head pointing upwards [Hazel] found himself gazing at the ridge, as over the sky-line came the silent, moving, red-tinged cumuli…. He realised now they were almost on level ground. Indeed the slope was no more than gentle for some way back along the line by which they had come; but he had been preoccupied with the idea of danger and had not noticed the change. They were on the top of the down.

Richard Adams, Watership Down – ch 18: on Watership Down

And similarly, when the Dawn Treader sails towards the Lone Islands (do we need to pause here and think of the untold story of Narnian colonialism? Is the story at all interesting, Mr Lewis?) the map serves to give us all an understanding of what can and what can’t be seen from the Governor’s residence when Caspian’s arrival threatens his position: it is, like Thorin’s map in The Hobbit, both a guide for us and a prop in the drama.

Sometimes – I would say very often – it’s not the bare narrative that needs them but the ethos of the world created. They are a kind of uber-illustration of the world of the story: they provoke question and exploration; they suggest a visit; they might provoke nostalgia. Le Guin’s Earthsea is such: an important extra in the telling of the story, illustrating distance, possible threat, possible alliances and cultural overlap: how close the dragons on Pendor are to little Low Torning is important in Wizard; their intrusion into the West Reach will return in the final book The Other Wind.

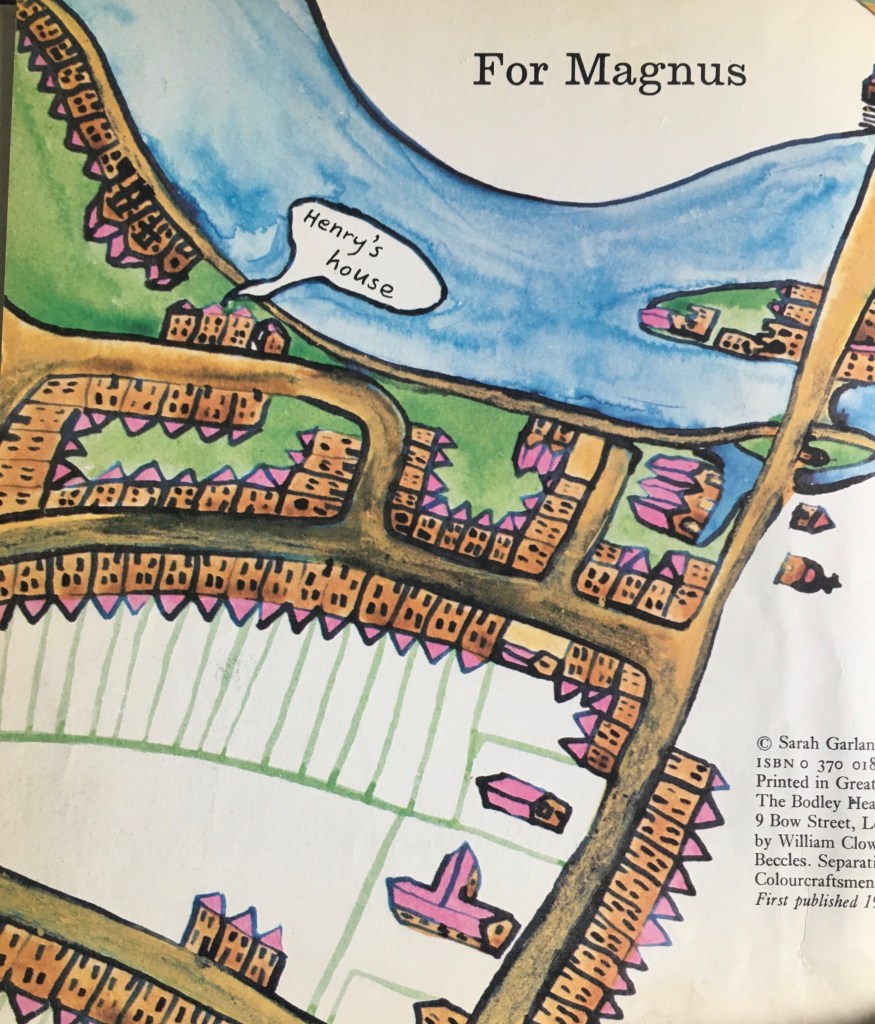

Maps of real places have a powerful pull – to visit, to return. It is their detail in part that powers up the nostalgia. Such is the power of a map that seeing Garland’s map in Henry and Fowler – which included the Nursery School my son had gone to to, close to where we had lived – was one of the tipping points that made us look at coming back to Oxford from Co Durham.

Pedagogically, fictional places with accompanying maps can allow a pause in the reading to explore, to ponder – a good map will have more than the simple route, but will invite the “what’s that?” “what if” questions that a text will propose in different ways.

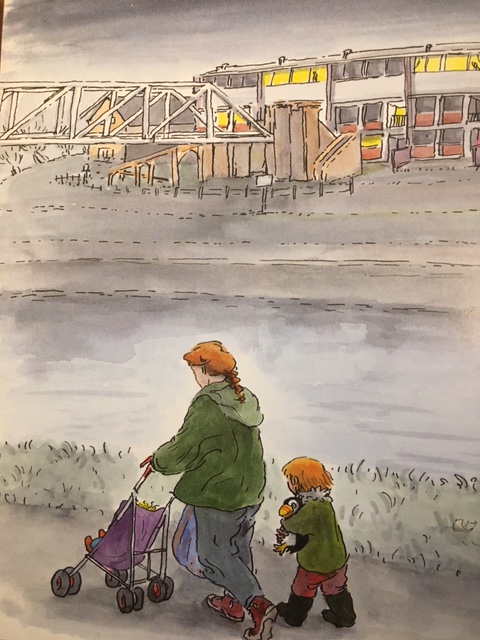

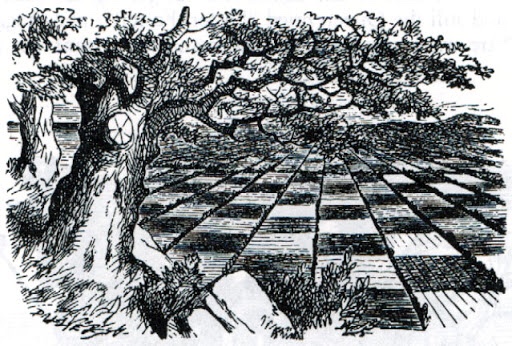

Lastly, then, here are some slightly different Oxford images: Tenniel’s view of the chessboard landscape in Through the Looking Glass; floods in Christ Church meadow; the bridge from Friars’ Wharf to the Grandpont suburb of the city. The first two images (l-r) relate to Lewis Carroll’s storytelling. The fantasy of the Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass worlds is based around the eccentricities of people the Liddell children knew in Oxford; this first view is, I think, based on the chequerboard of small fields and dykes and ditches within a mile of Christ Church towards North Hinksey. The second is a flood on the marshy fields between Christ Church and the Thames – and in literary terms we can think of the floods in the Sheep Shop in Wool and Water, but also, now, of Malcolm’s eponymous little boat in La Belle Sauvage. The third – again, the Thames, in the area explored in many of the works of Sarah Garland – for our children’s journey into town this was always the Polly Puffin Bridge, after the illustration in Garland’s lost-and-found story set in the city.

And the final (huge) task is to ask a set of comparative questions about the relationship between map and illustration. Are illustrations – the Tenniel or the Garland here, for example, doing the same kind of job as a book-map? Are maps from a stricter cartographic discipline (such as OS Maps) doing a different job again? What does seeing the “real” place add to our appreciation of the author/illustrator’s work? I love Christ Church meadow in frost and flood and sun – but do I need to see it in photographic form or in real life to appreciate the strange chaos of the flood in the Sheep Shop? I sometimes want(ed) to say to crocodiles of tourists “This isn’t Hogwarts, really, you know” and “This isn’t really Wonderland.” And then I see that tourism is looking to show off the “real Hundred Acre Wood.” The rant would be a digression – and after all, what were we doing in Thursbitch or Ludchurch?

I think that depictions of South Oxford – the map from Henry and Fowler, the same towpath in Polly’s Puffin – give us detail both help with what Molly Bang in Picture This calls the emotional content of pictures, something which can be done in all sorts of ways, and which visual art, hand-in-hand with text (what Mat Tobin calls a symbiotic, fruitful relationship), does powerfully. Maps in fiction texts are a subtle, shifting part of this symbiosis: the mutual enrichment that works well in good quality fiction can go further when a map illustrates the place.

Oh enough: I’ll simply cite Mat’s blog here:

I always call on Maurice Sendak who said: ‘I wanted at all costs to avoid the serious pitfall of illustrating with pictures what the author has already illustrated with words’. A great picturebook is one in which the words and the pictures work together to tell the story but they never say the same thing.

Mat Tobin “Why Picturebooks matter” http://mattobin.blogspot.com/2015/06/why-picturebooks-matter.html

…and end with the emotive map that has been at the back of my mind since I started writing this: Moominvalley. Even more than Milne and Shepard’s 100 Acre Wood Tove Jansson’s valley was a map for my play.

Nice blog

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed reading this very much, thank you.

LikeLike

You say this post jumps about a bit, but after taking some notes — more of a spidergram or mind-map really — I find what you have to say very coherent.

Though you start with a map’s function you pretty soon talk about different audiences and their responses: the Reader, the Writer, and the Critic. You then go on to their ethos and emotional qualities, before talking about the relationship of the map with the text and with other illustrations.

As a schema for critical evaluation of cartography (and other bird’s eye views) in fiction and non-fiction this is ideal for me personally when I go on to complete my Aiken discussions, and mapping in other fiction I’m reading. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am seriously pondering a book tbh: first step is a journal and book title crawl.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If it helps I could recommend some titles, though I fear you may already know most of them.

LikeLike