There was a time long ago – say, last Sunday afternoon – when nipping off for a run seemed easy and natural. And on Monday, when Jeff and I went for a walk – well, it seemed a normal thing. Bloke. Dog. Biscuits. Sunshine. The political clouds of isolation and the warning that people had to be more responsible were looming, but dogs gotta walk, and man’s gotta be sensible about “social isolation.” That seemed about it.

Jeff the dog and I went to South Park and Warneford Meadow. We got muddy, he more than I, we looked at the various corvids and the people playing basketball, he ate dog biscuits and I didn’t, and we were sensible about keeping ourselves to ourselves. We didn’t do the reckless “last weekend before we have to be indoors” congregating, but yes, it seemed that keeping to guidelines was easy. A new politeness was emerging around how far apart we needed to be from people we passed, it’s true, but in any case they weren’t people either of us knew, not even nodding acquaintances. A quick chat with the basketballers a good 4m away and then we moved on. We got closer to magpies, to be honest. Three for a girl, if I remember rightly.

Only with yesterday evening’s pronouncements did that mood really change, and I think in retrospect we pushed it a bit. Maybe it was my day’s exercise. It will have to stand as such.

Wind back a week and I am with Mat high on the Downs, and you could not wish for a lovelier day. Sunny again, breezy, a sharp-eyed, sharp-minded kestrel of a good friend, everything bright and fair. As I discussed here, human relation to place is, for Robert Mcfarlane, grounded in language; but language is itself grounded in relationship. I’m coming back to this.

Back to the Friday before and Lizzie, Maggie and I walk through the Aberlady nature reserve and across the beach to Gullane. A bright sun, a brisk wind. Family enjoying one another’s company.

But these are not excuses to show snapshots. What is it that gave these trips significance? Why feel better after them? They both lacked the challenge of Rob Macfarlane’s exploration of the treacherous Broomway or even the experience of our face-to-face encounter at Ludchurch. What is it that some trips into the outdoors bring? and how do we represent that in time and place without it being, like these photos, just a grown-up version of What I did on My Holidays?

The absolutely seminal book on the psychology of the outdoors for me is the 1989 book The Experience of Nature, by Rachel and Stephen Kaplan. In it, they explore dimensions that may provide a framework for how “nature” helps and supports psychological wellbeing. Extent; fascination; action and compatibility. Because their work looks to the “wilderness” they address the nation of escape as well, which they view with some caution because it has in it “an absence of some aspect of life that is ordinarily present and presumably not always preferred.” I can see their point, but given that it is early work (thirty years ago) and has been superseded in many ways (partly by the new nature writing itself), I want to raise the question of escape with someone. Here, further off on the Aberlady sand dune, is Maggie; Mat not only drove the two of us to Uffington, his insights enriched our visit. We are “political animals” – not because we are forever tuned into the depressing power games (or, if you like, selfless and inspirational leadership) that cram our news until we cannot see what’s actually happening – but because we are defined by how we live in the company of others. I go out on my own but with me come meetings to have, people I want to see (or don’t), ideas to bounce off others. I bring the city with me. And similarly I contend that a visit to Uffington means I am “with” (metaphorically) Rosemary Sutcliff, or that to go to Ludchurch “with” Alan Garner is not to travel alone. In some ways, the accompanying author or characters provide what the Kaplans call action and compatibility, and of course are the spur to action via the notion of fascination. We go “Backpacking with the Saints” according to Belden Lane (article here; link to the [excellent] book is here. Name the saints that come with you.

Lane, a “scholar in recovery” takes with him insights from the Desert Monastics and “a few lines of Rumi” and is wedded to the silence that wilderness can bring. Not as far into my recovery I have taken Gawain, most recently Sun Horse Moon Horse and the Land of the White Horse. Somewhere in my mental backpack are lines and vistas from writers such as Robert Macfarlane, C S Lewis, Oliver Rackham…. This isn’t a boast: I sometimes wonder whether I could leave them in the car. Would this then be more of an escape, or given the liberating nature of some of this writing, less of one? And what about extent? Do we need the wide open wilderness of the Ozarks are we OK with the view from the White Horse down into the farmlands of Oxfordshire and Wiltshire? I think of Aberlady, where I have no literary baggage to bring: an escape, as the Kaplans would see it from particular content, “a rest from pursuing certain purposes.” I wonder if writing about his wilderness hikes took the edge off the experience from Beldin Lane…

But for the trips that fall under the Wild Spaces Wild Magic umbrella I really have to take the authors firmly in my hand and my mind: last week for example I was reading the episode of Lubrin Dhu’s planning of the White Horse from Rosemary Sutcliff and looking for where she might have sited the Wych Elm. She comes with me and by extension the characters she calls into being; David Miles comes with me – my copy of his book has a smudge of Uffington soil on the page of his site plan (p101, if you’re interested); Mat of course comes with me. Identifying where this Wych Elm might have been, we find some wild apple trees by chance and wonder: are these the inspiration for the sacred apple trees in Sun Horse Moon Horse?

Social aspects of serendipity (see for example Morrissey’s “An autoethnographic inquiry into the role of serendipity in becoming a teacher educator/researcher,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 2014) seem to me to work alongside the changeability of being outside. Less is in the enquirers’ control, expectations have to change. Two pairs of eyes are able (sometimes) to be more alert to these changes: sagacity (Morrissey again) enhances serendipity but are two heads better than one? If we are aware of the dangers of shoring up each other’s ideas, might collaboration, like identifying mistakes (Morrissey) “also uncover for the researcher… fears, preconceptions or beliefs …of which he/she had hitherto been unaware”?

And if we are accompanied by the cloud of witnesses from literature – such as nature writers and their places, fiction writers and their characters – then we might address two notions (or one single notion with two aspects? I’m not sure as I write) of psychogeography and autoethnography. How much, in other words, does setting (in its broadest sense) and personal history of setting enhance or detract from personal reading of landscape? I am conscious of the dilemmas where Dyson writes “In recognising that I was a subject and an object of the research I realised that at the same time I was and could be both an insider and an outsider within the culture that I was investigating.” (From his article My Story in a Profession of Stories: Auto Ethnography – an Empowering Methodology for Educators, https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/ 2007). I rejoice in being on the Downs with Mat; I am very glad we have purpose in a book I love; I am exhilarated in the chill breeze and bright sun. To change from his journey metaphor to one of wind or water, being the reader and a colleague in an investigating team involves recognising how all sorts of things flow over one another: the reader and her/his history; the researcher and her/his concerns and limitations; the authors under investigation, their sources, their motives, their depiction of place and character; and being a research partner multiplies these complexities. For me this links with Rob Macfarlane’s lines from his introduction to The Living Mountain:

…the world itself is therefore not the unchanging object…but instead endlessly relational. It is made manifest only by only by presenting itself to a variety of views, and our perception of it is made possible by our bodies and their sensory-motor functions… We have come increasingly to forget that our minds are shaped by the bodily experience of being in the world – its spaces, textures, sounds, smells and habits…

We are human, language-loving and people-loving; we are also placed: physically located on a windy ridge above a deserted farmhouse in the Peak district, or searching for a tree that may never have been at the foot of the Downs.

To conclude with Belden Lane, who may be close to an answer here (I know I’m not): The Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset once said, Tell me the place where you live, and I’ll tell you who you are. I think he also could have said, Tell me the place to which you are drawn, and I’ll tell you who you are becoming.

In the church the silent near-dark was stunning, and all those poems from all those Thomases, Thomas Merton and R S Thomas and T S Eliot (not to mention Dylan Thomas’ “close and holy darkness”) were somehow at my elbow. And maybe the incense smudge of a memory of the church when I was a child, after Compline and Benediction, or the quiet of Magdalen after Night Prayer…

In the church the silent near-dark was stunning, and all those poems from all those Thomases, Thomas Merton and R S Thomas and T S Eliot (not to mention Dylan Thomas’ “close and holy darkness”) were somehow at my elbow. And maybe the incense smudge of a memory of the church when I was a child, after Compline and Benediction, or the quiet of Magdalen after Night Prayer… Well, actually my task was to tidy the absolute dog’s breakfast I had made of the hazel I had undertaken to

Well, actually my task was to tidy the absolute dog’s breakfast I had made of the hazel I had undertaken to  I am, because of how my mind works, really quite moved by the metaphor – but recognise that I need to get to work. The two rods have, I guess, been working at this for years, but now I need to get cutting. I sort of hope that I can cut the fusion out as a whole piece (but in the end I can’t)… but the time the hazel has taken and the time it takes my saw to undo the fusion seem out of all proportion.

I am, because of how my mind works, really quite moved by the metaphor – but recognise that I need to get to work. The two rods have, I guess, been working at this for years, but now I need to get cutting. I sort of hope that I can cut the fusion out as a whole piece (but in the end I can’t)… but the time the hazel has taken and the time it takes my saw to undo the fusion seem out of all proportion. Why does the glorious

Why does the glorious

He has, it seems, nothing left, although the book and Arthur’s lessons about what it is to be human have some way to go. The unrequited desire, the longing for fulfilment, for liberation: exhausting.

He has, it seems, nothing left, although the book and Arthur’s lessons about what it is to be human have some way to go. The unrequited desire, the longing for fulfilment, for liberation: exhausting.

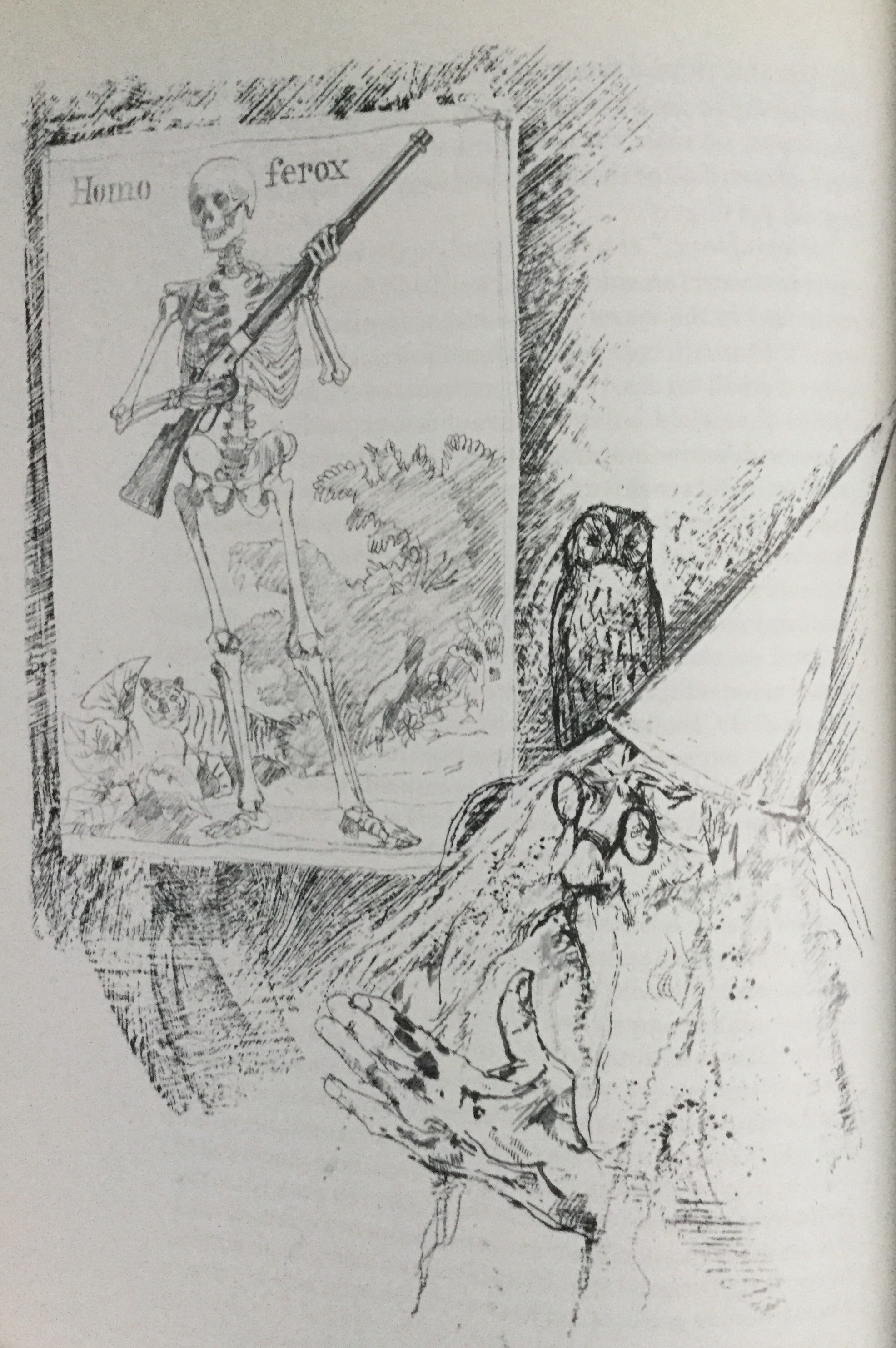

The gentle, bookish comedy aside, this allows Merlyn the painful knowldege that Arthur is to die in battle the next day, and for White/Merlyn to comment on fascism and communism, and for King Arthur, lost and tired, to ponder his path, as (with the the magician’s assistance) he visits ants, geese and takes advice from the donnish Badger and the Plain People of England in the shape of the Hedgehog… What makes Arthur Arthur? What makes a Human Homo Ferox rather than Homo Sapiens? Facing defeat of everything he thought he stood for, yet surrounded by his animal advisers and under the magic of the querulous Merlyn (beautifully depicted by

The gentle, bookish comedy aside, this allows Merlyn the painful knowldege that Arthur is to die in battle the next day, and for White/Merlyn to comment on fascism and communism, and for King Arthur, lost and tired, to ponder his path, as (with the the magician’s assistance) he visits ants, geese and takes advice from the donnish Badger and the Plain People of England in the shape of the Hedgehog… What makes Arthur Arthur? What makes a Human Homo Ferox rather than Homo Sapiens? Facing defeat of everything he thought he stood for, yet surrounded by his animal advisers and under the magic of the querulous Merlyn (beautifully depicted by