To reflect on the moving Corey’s Rock by Sita Brahmachari and Jane Ray has required a number of shifts in my thinking. I’ve had to screen out some of the praise for the book as well as the discomfort I feel at a personal level for a subject that – in part at least – touches my own life. There are already confusions here, and what I want to do is to return to the questions of ambiguity I’ve looked at before (in fact just over a year ago in my post Understanding).

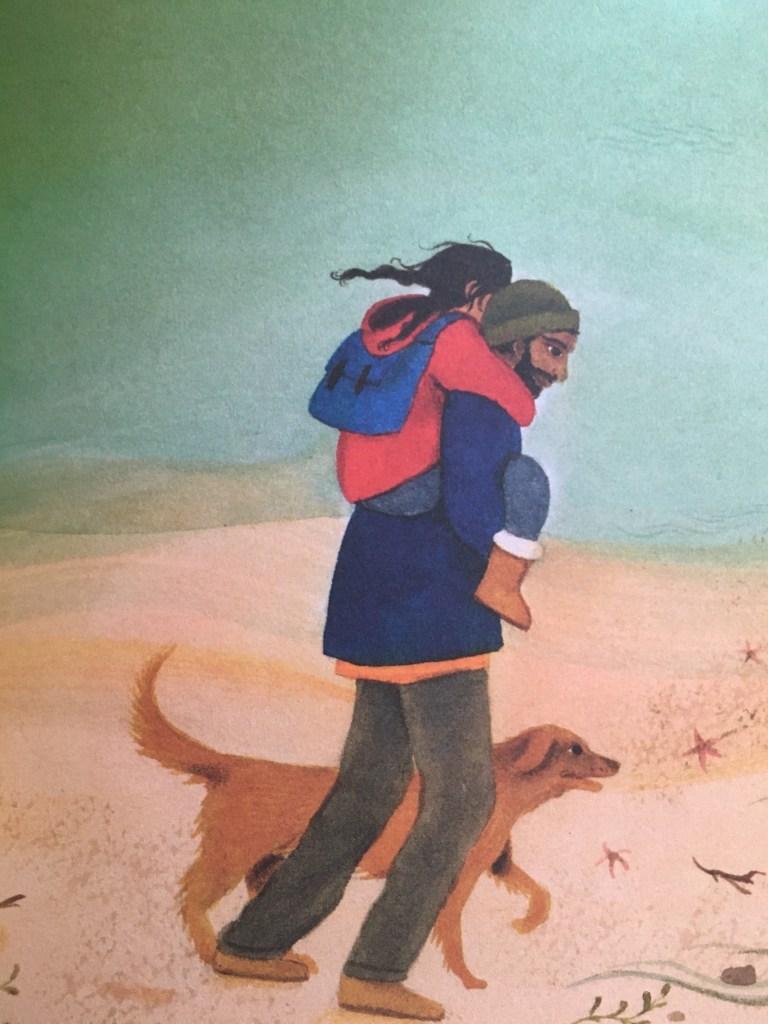

Corey’s Rock tells an uncomfortable story. Isla, the young first -person narrator, has returned to the island where her mother’s family have roots. In the aftermath of the death of Corey, Isla’s younger brother, the family of four – Mum, Dad, girl and dog – are a family seeking, in Auden’s words, locality and peace. The narrative at its simplest is about the weeks in which Isla begins to settle into her new life while mourning her brother.

But I see that I have already strayed away from the simple into the complex, and in referring to Auden I have returned to my own confusions, and a post in which I look at the

the cramped frustration of attempting

the jigsaw with pieces missing

And if the posts from that time are about a lost me, this book is a story of a lost family.

So I think there are three sets of confusions to be addressed here: the ambiguities of the text and illustrations; the complexity and detail of narrative and art work; the twinges and uncertainties of the reader.

They are not all things we should fight shy of: life is confused; endings are uncertain. If the current crises in health, society and the economy (insofar as they can be disentangled) can teach us, we are an uncertain bunch: too reflective to suffer dumbly, but unable to make much sense of sudden changes, sudden downturns in our fortune. This is not always to the advantage of the writer, who has to contend with issues of clarity. Jenny Nimmo writes a piecemeal and sometimes unclear narrative when she looks to set out the relationship between the magic world and our world in The Snow Spider; Sita Brahmachari does the same with a similar brief: how to look at a child’s grief through myth and landscape. The issue, it seems to me, is connected with the genuine confusions in the minds of Isla and Gwyn – and the pain of their adults. Ivor, Gwyn’s father, is the more confused of the two dads, lost in his anger as much as Bethan was lost on the mountain; Isla’s father (and some cost to himself, I think), sighs as he tells his daughter “You know Corey can’t come back, don’t you?”

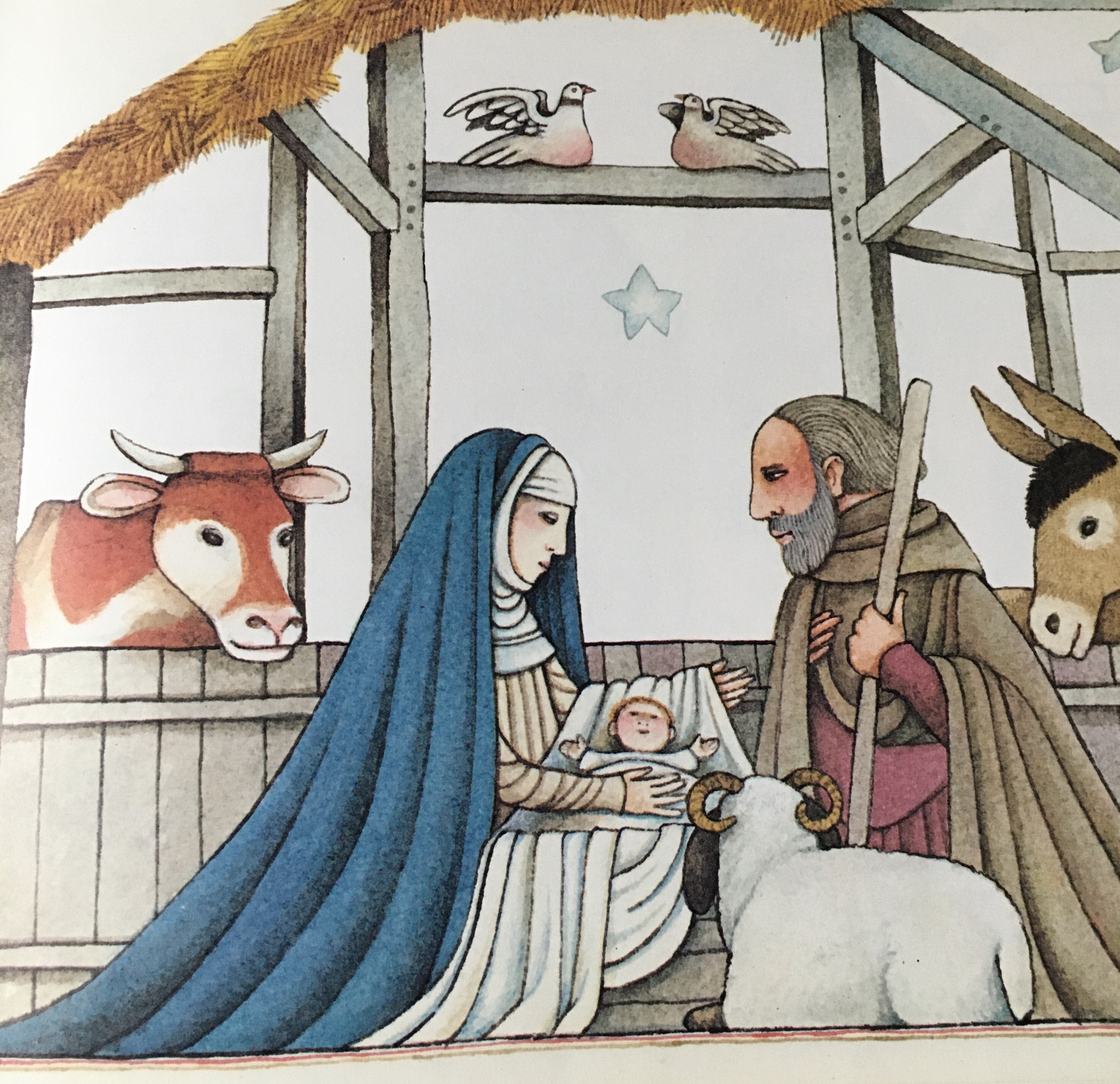

The truth does not make him any less beautiful or eloquent: Jane Ray’s luminous artwork gives him soulful eyes and a deep connection to his children and Sita Brahmachari gives him the best lines:

“How deep does the colour go?” I ask Dad.

How deep is the sea,” he answers.

He is an archaeologist with the soul of a poet. Kathleen Jamie, meeting him on a beach in the bleak north of Scotland, would have found a friend.

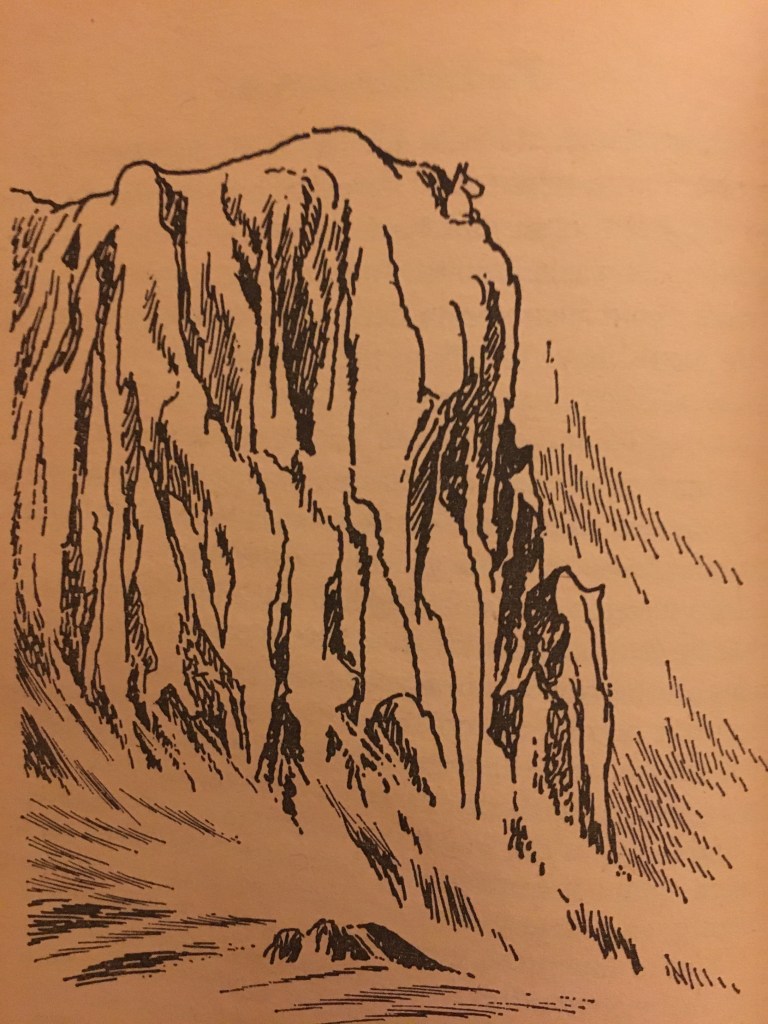

Back to my three confusions: I suppose I am trying to distinguish in my own mind between what seems the author’s deliberate blurring of edges (which is as much at the heart of this as it is David Thomson’s classic People of the Sea and the film Song of the Sea) and the fact that I am not (or not yet) at ease with the rich complexity of the story Brahmachari is telling. Shapes shift, roles move, tragedy and freedom walk hand in hand, and in this story we trace other themes, too, besides myth and landscape: race, disability, belonging, refugee children washed up on the shores of Europe; the roles of incomers in an island community; a mother coping with grief and a father’s efforts to keep his family whole; and the big question of little Isla:

Do you think this island will make us happy again?

Have the author and artist been over ambitious, or is it, perhaps, that I don’t feel able to embrace this complexity? I struggled with this on my first two readings, but then was struck by the Celtic knotwork on one of the double-page spreads, and thought of those complex interweavings that are part of so many pre-conquest crosses, ornaments (like this from a Viking grave in Orkney) and tombs and manuscripts – and I honestly think this was my misreading. This is an ambitious book, but look at Sendak (link here to the haunting and complex My Brother’s Book, again a richly illustrated and complex text about death); Foreman; look, even at the stories of Katie Morag and her own island life. I know picture books and richly illustrated texts aren’t always easy. Of course I know that.

So what was my problem here? My third confusion. It is possible for a story to be poorly written, badly drawn: in my teaching on a module called Becoming a Reader we would look at texts with ideologies long dead, books with clumsy pictures or inconsequential, often derivative stories. Corey’s Rock is not one of those, although the threads of detail take some following. The third confusion is where the reader looks but does not see how those threads might go.

Because in the end there are more and more threads to follow: where author and artist brings their research, their pasts (including their past work: the dad in Corey’s Island recalls – although not exactly – the beautiful, caring father in A Balloon for Grandad)… or where a reader’s own reading past or visits to a place or similar sadnesses lead off in the wrong direction.

So to end, not in any way to try and trump the painful story at the heart of Corey’s Rock, but maybe to explain part of my confusion as I read and re-read it, joining in the sea song of all those times Isla’s family walk along the beach or look out for the bobbing head of a seal, is one of my twenty-year old poems for our son Theo.

Recalling you is a daily conjuration. In solitude

I know my sadness, know your face, but you appear

where least expected: at the corners of sleep;

at the bruise of unkindness; in a flower

unlooked-for, by a cliff’s edge.

Today I called you,

throwing a stone

into the receding tide,

trying to write your name in the wet sand;

but as I made the first stroke, crossbar of your T,

the wave returned,

unbidden, sudden –

And the mark my writing didn’t leave was you.

Why does the glorious

Why does the glorious