I am reading T H White’s The Book of Merlyn again after a long break.

The paper trail is not edifying so maybe it needs acknowledging – at least, the messiness needs some acknowledging. It is a mess of the biographies of two men: William Mayne and T H White. There remain all sorts of issues about how we celebrate the creativity of people whose personal lives did not measure up to the standards we would wish. That is at least some acknowledgement…

I came back to the Sword in the Stone again having read William Mayne’s The Worm in the Well, which echoes it. I asked when I’d read it if Mayne’s flaws deafen me to his message of reconciliation and renewal; I find myself asking over and over the same with T H White – something I was alerted to in Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk. But for the purposes of this blog post (which will largely be quotation from the Book of Merlyn) I am going to set aside the author and look at the text.

I know I’ve written about the magic patriarch before, when Merlin, Merriman et al have come up from my reading (here, for example, where I mention White explicitly, and then here, for the “humanist rabbit pulled from a transcendental hat,” and most recently here) but Merlyn – note the spelling – is here at the moment because of T H White’s lost-and-found masterpiece and its subject. Setting aside the moving first sections, the re-encounter of Merlyn with his former pupil (now beaten and old and depressed) the substance of the story brings us to Badger’s sett, to, in effect, an Oxbridge Senior Common Room in the grand old style, the Combination Room, where Arthur is tasked by Merlyn and the animal committee to make sense of the human condition, in the last night before Arthur’s final battle.

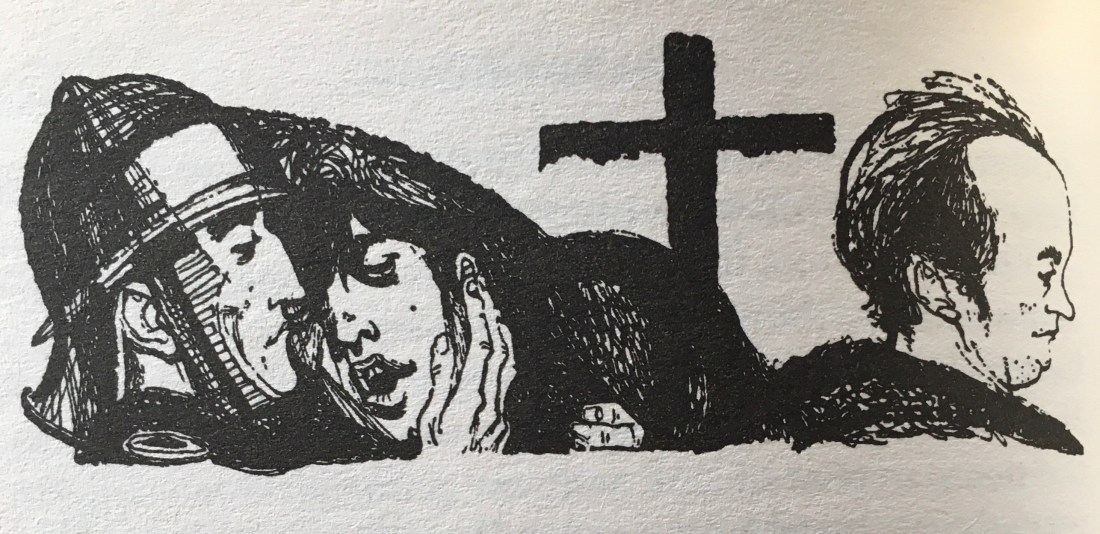

White’s construction of Merlyn’s prophetic powers is that he is living his life in the opposite direction to the rest of us. Merlyn has known the insanities of C20th totalitarian regimes (White wrote the book as part of his struggle about whether he should maintain his pacifism), refers affectionately (but not without criticism) to his friend Karl Marx, and gets muddled in trying to explain to Arthur that the whole story they are in is on a book – the book I am holding.  The gentle, bookish comedy aside, this allows Merlyn the painful knowldege that Arthur is to die in battle the next day, and for White/Merlyn to comment on fascism and communism, and for King Arthur, lost and tired, to ponder his path, as (with the the magician’s assistance) he visits ants, geese and takes advice from the donnish Badger and the Plain People of England in the shape of the Hedgehog… What makes Arthur Arthur? What makes a Human Homo Ferox rather than Homo Sapiens? Facing defeat of everything he thought he stood for, yet surrounded by his animal advisers and under the magic of the querulous Merlyn (beautifully depicted by Trevor Stubley), Arthur, the aged king, is exhausted:

The gentle, bookish comedy aside, this allows Merlyn the painful knowldege that Arthur is to die in battle the next day, and for White/Merlyn to comment on fascism and communism, and for King Arthur, lost and tired, to ponder his path, as (with the the magician’s assistance) he visits ants, geese and takes advice from the donnish Badger and the Plain People of England in the shape of the Hedgehog… What makes Arthur Arthur? What makes a Human Homo Ferox rather than Homo Sapiens? Facing defeat of everything he thought he stood for, yet surrounded by his animal advisers and under the magic of the querulous Merlyn (beautifully depicted by Trevor Stubley), Arthur, the aged king, is exhausted:

There was a thing which he had been wanting to think about. His face, with the hooded eyes, ceased to be like the boy’s of long ago. He looked tired, and was the king: which made the others watch him seriously, with fear and sorrow.

They were good and kind he knew. They were people whose respect he valued. But their problem was not the human one…It was true indeed that man was ferocious, as the animals had said. They could say it abstractly, even with a certain didactic glee, but for him it was the concrete: it was for him to live among yahoos in flesh and blood. He was one of them himself, cruel and silly like them, and bound to them by the strange continuum of human consciousness…

One of them himself. Politics, ethics, where to belong and whether to resist: these are not abstractions for White (in exile in Ireland in 1942 as he writes), or for Arthur – or for us. As he writes, Tolkien’s Fellowship are paused at Balin’s tomb in Moria, Lewis’ protagonist in The Great Divorce is sent back to everyday life in Oxford rather than face the terrible sunrise of the parousia: it is a decade of loss and darkness and doubt. Life should have been sorted in the War to End Wars that ended in 1919 – and hadn’t been. Arthur continues to ponder:

…he had been working all his life. He knew he was not a clever man.… Just when he had given up, just when he had been weeping and defeated, just when the old ox had dropped in the traces, they had come again to prick him to his feet. They had come to teach a further lesson, And to send him on.

But he had never had a happiness of his own, never had him self: never since he was a little boy in the Forest Sauvage.… He wanted to have some life; to lie upon the Earth, and smell it: to look up into the sky like anthropos, and to lose himself in clouds. He knew suddenly that nobody, living upon the remotest, most barren crag in the ocean, could complain of a dull landscape so long as he would lift up his eyes.

And I know how he feels: to have some life seems to me to be a core desire – certainly for Arthur, whose life has, throughout the books, been so rarely his own.

Is this last part of this post a spoilier? I find it hard to say: the book has a moving ending, the various endings to the legends providing their own kind of speculative fiction. The sleeping king of so many folktales? Avalon? Edinburgh? and White has to make his own move about his position on war and resistance. But before he does, he finds space for his own legend of Arthur Rex quondam et futurus:

I am inclined to believe that my beloved Arthur of the future is sitting at this very moment among his learned friends, in the Combination Room of the College of Life, and that they are thinking away in there for all they are worth, about the best means to help our curious species: and I for one hope that some day, when not only England but the World has need of them, and when it is ready to listen to reason, if it ever is, they will issue from their rath in joy and power: and then, perhaps, they will give us happiness in the world once more and chivalry, and the old medieval blessing of certain simple people – who tried, at any rate, in their own way, to still the ancient brutal dream…

But defeating the barbarities of Attila or Sauron or Mordred remains only a hope, an aspiration, and I return (as ever) to Susan Cooper’s bleak but rousing Merriman:

You may not lie idly expecting the second coming of anybody now, because the world is yours and it is up to you.

A different , maybe more grounded Merlin and a different hope to the poor hope of the exiled White.

The nights close in, the socialisation is indoors, defined, more visible, with the freedoms of warmer weather lost or at least traded for friends and firesides. When C S Lewis envisages this in the hearts of his heroes in

The nights close in, the socialisation is indoors, defined, more visible, with the freedoms of warmer weather lost or at least traded for friends and firesides. When C S Lewis envisages this in the hearts of his heroes in

this morning showed her perspicacity. In distinguishing (as she did) between “fun” and “engagement” she laid bare one of the most important issues facing outdoor education that follows something of the Forest School ideal. Primarily child-led, but a powerful element in enriching school-based learning. Not every student can do this so early in their course; not every teacher or pedagogic critic can do it either.

this morning showed her perspicacity. In distinguishing (as she did) between “fun” and “engagement” she laid bare one of the most important issues facing outdoor education that follows something of the Forest School ideal. Primarily child-led, but a powerful element in enriching school-based learning. Not every student can do this so early in their course; not every teacher or pedagogic critic can do it either.