Who makes learning desirable?

It is a sunny day, probably in 1997 or so. Despite a visit from my Early Years adviser – at least, I hope it was “despite” rather than “In a desperate attempt to show said adviser that a teaching Head could work effectively in the nursery outdoor environment” – I was out in the garden, watching, supporting, intervening and choosing not to intervene. I remember it involved a lot of transfer of water from the outside tap, while those not playing in the sand and water were climbing trees, running a shop… Hesitant children were being given literally a helping hand to overcome their fear of mud; more confident Wild Things were being guided towards a way of playing that was more inclusive; a small group were playing a game we had developed together called “1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – SMASH,” in which some children were waiting until five sandcastles had been built before they could jump up and down on them. All of these were, of course, of limited success: no single activity is likely to produce a piece of learning, perfectly formed and squeaky clean. Learning takes time, repetition, commitment from adult as well as child.

At the time – maybe as now – there was some debate about curriculum content, aims, approaches. We were moving (this is a truncated version of the development) from the Desirable Learning Outcomes through the Curriculum Guidance, until we came to the revision of the Early Years curriculum under the forbidding title of the Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage, revision of which has brought us to where we are now, with all its supporting guidance. Maybe this fluctuation of emphasis and debate is how it should always be – provided it doesn’t slide into a power struggle like some kind of Tudor court politics, where which faction has the ear of the powerful is the indicator of what is “right” or “wrong.” At the time, in the late 90s, however, Early Years education felt embattled more than challenged, and I remember asking Julie – yes, the adviser was Julie Fisher, sharp-eyed and thoughtful as ever – whether she thought the “classic” state nursery education model had had its day, if we were looking at a model that was something of a creature on its way to extinction. “Not a dinosaur,” she replied, “but maybe an endangered butterfly.”

And part of me wondered how long we had.

Last week, however, Julie was kind enough to give Maggie and me a copy of the fifth edition of the book for which I think she will be remembered: Starting from the Child? She continues to write with the passion of a conservationist, but goes much further than simply wishing to preserve a fading set of practices.

Each edition has been worthwhile, but the new, fifth edition has some really interesting things to say. I don’t intend to make a line-by-line textual analysis of Prof Julie Fisher’s fourth and fifth editions of Starting from the Child, except to notice that the question mark has come and gone across the editions and through the years. The question mark notes the approach taken in the latest edition: Julie is clear from the preface on:

I believe that recent policies and expectations pertaining to early childhood education now make it a challenge to always keep the child at the heart of best practice. SFTC?5, p xvi

The quiet(ish) shift away from what we might have thought of as child-initiated learning came more vividly to my attention when Prof Kathy Sylva was presenting findings that were part of the EPPE project, and a transcript of a (pretty dire) group time in which the adult kept peppering her attempts to keep the children on task with “I need to you know…I want you to know.” It was a far cry from the beautifully descriptive blog post in which Julian Grenier played with the ideas of a child enrgrossed in the spider he had seen at the tricky moment of transition:

“He had held onto something that was fascinating him, despite his upset, and he had wanted to share it with [his key person] once he felt calm enough.”

http://juliangrenier.blogspot.com/2012/12/magical.html?m=1

The little boy’s insistence on retuning to the spider meant that the teacher felt overcome by a child’s sense of wonder. It’s a lovely piece of writing, made all the more so by the fact that so many of us, alert to a key interest or moment in a child’s day, have seen similar incidents. Even back as far as Margaret McMillan herself (and in her particular style) the children experience the garden with wonder:

Gold and green, purple and white, rose and blue, meet us at every step : and the children look at this newborn wealth of colour with wonder. It is surely the moment to fix these glorious tints and shades in their memories and make of them living memories.

Margaret MacMillan The Nursery School (1919) p139

In more modern parlance, this is an important part of what Annica Lofdahl describes as

the teachers’ efforts to develop a pedagogical environment that creates positive opportunities for learning and development.

Annica Lofdahl, “Who gets to play?” in Brooker and Edwards Engaging Play (2010, p123)

Time and again the pedagogical decisions of the adults are about creating positive opportunities for children to greet their environment and their important people (children and adults) with questions about how the world works. Julie puts it clearly:

Curiosity is provoked by a high quality environment in which children pose their own questions

SFTC?5 p27

We set up an environment in which the children can move from attachment to home people to adults and children they can trust, in an enviornment that allows curiosity to flourish. Not just busyness, note: a place where questions are at home, where adults build on what they already know of a child. This is how we “start from the child.” It is not a step-by-step “now you learn this;” equally it is not a vague wandering round a nursery with a key worker trying to entertain or distract the child. No: Julie is looking for a patient building on interests known from home, an understanding of how children learn and how sequences of learning and development work.

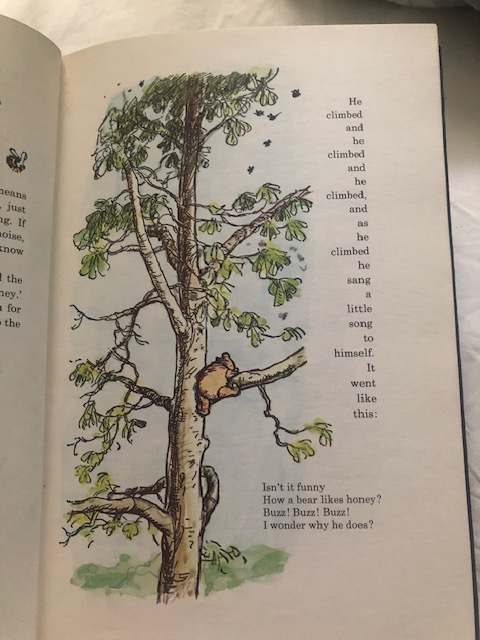

It is in the opening pages of Starting From the Child? Ed 5 (SFTC?5) that Julie talks about this in terms of the child being intrigued and curious. Likening young children’s learning to a traditional jigsaw, Julie – ever the one to choose an engaging image – points out how a child turns the piece round, examines it with patience. The adult is watching, maybe commenting or questioning, but fully grasping that this is learning prompted by the child’s own curiosity. Where then is the adult?

It is the skill of the educator to be aware of the pieces of the jigsaw that the individual child already has in place and whether or not they have fitted the pieces together correctly. If they have not, then supporting the child to review the construction of their cognitive jigsaw is as delicate and difficult an operation as persuading the child to remove a piece of misplaced wooden puzzle… The inappropriate imposition of connections can lead to the learner becoming confused and disaffected…The effort to make connections is all the more likely and all the more successful when a child is motivated to do so.

SFTC?5 p28

This seems to me to at the heart of what Julie Fisher is getting at, with the title of her book. It is by no means a worn-out phrase, but one that needs regular reappraisal and challenge. Starting from the Child might mean simply

What do I want this child/these children to learn and how will they best learn it?

SFTC?5 p67

Have I reduced this to such simplicity that this looks like a book of obvious assertions? It certainly isn’t that. When Julie explores fundamental differences between the adult and the child curriculum she is clear that

…it should never be assumed that learning [sc for every child] will be equally sequential. Each child’s sequence will be highly idiosyncratic according to the knowledge and understanding they already have and that they bring with them to the learning situation.

SFTC?5 p114

And this underlines what she has written earlier:

As educators we join the child some considerable way along their learning journey.

STFC?Ed 5 p11

And this previous experience – which can be positive or negative – has to be seen as fundamental to the learning attitudes and processes the child brings. Observation – and effective communication with parents and previous settings a child might have engaged with – allows us to hone in on what a child is motivated by. The chapter called Whose curriculum matters? has sections and examples on how context allows children to revisit and apply new knowledge and understandings. (SFTC?5 p116)

Yet – and this is where I have to finish – Julie would not want the reader to think this is something wholly in the hands of the child or children any more than it is in the hands of the adults in an Early Years setting, but often takes places in the negotiated space of a rich and curiosity-provoking environment. I love the section (SFTC?5 pp128ff) in which she exemplifies adult-led learning being used in child-led activity, and vice versa, child-led activity being picked up and extended in an adult-led context.

We are back in my nursery school in the nineties: how we move water with buckets and guttering was important to the children and the language was – thanks to the adults (not just me – but teamwork and shared adult expactations makes a whole different blog post) – extended and enriched by modelling, deep questioning, shared attention and excitement. The same was true with the sandcastles, the shop and the chasing games.

Having different purposes and different outcomes does not preclude adults and children from learning from each other’s plans and outcomes. Each must be given time to flourish and to conclude…

What must be achieved is a balance – a balance ensuring what children are to learn influences how they learn. But primarily, all that is known about the child as a unique individual is the starting point for planning the curriculum – whoever leads and whoever follows.

SFTC?5 pp129, 130