Some thoughts on picturebooks about death.

In my Twitter bio I often have some mention of my interest in picturebooks along the lines of looking for answers to big questions in small books. The review of Yumoto and Sakai’s The Bear and the Wildcat that I did recently for Just Imagine raised more questions about maybe the biggest of big questions, or at least the biggest in terms of what can be depicted in picturebooks: how do we deal with death?

For me, at any rate, The Bear and the Wildcat stands as one of the greats. Plain text, subdued artwork, and just enough raw emotion to take the reader somewhere uncomfotable. Why is the discomfort important?

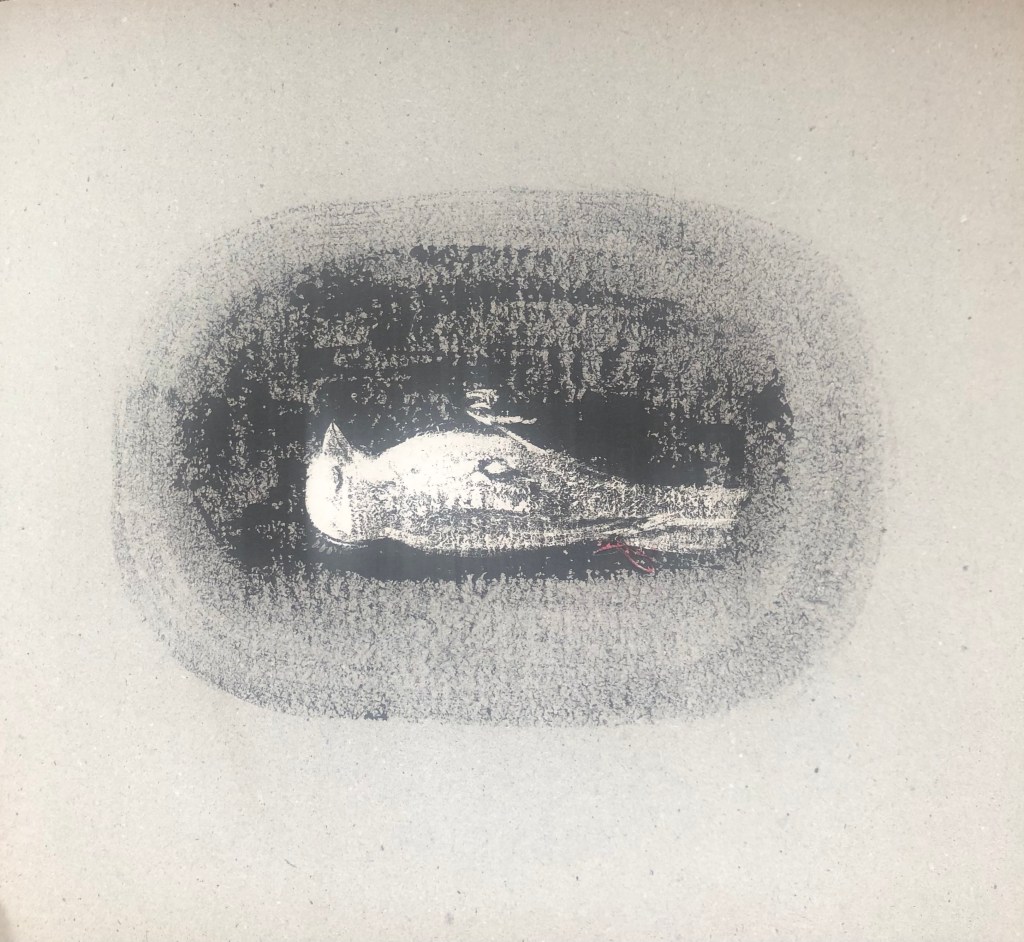

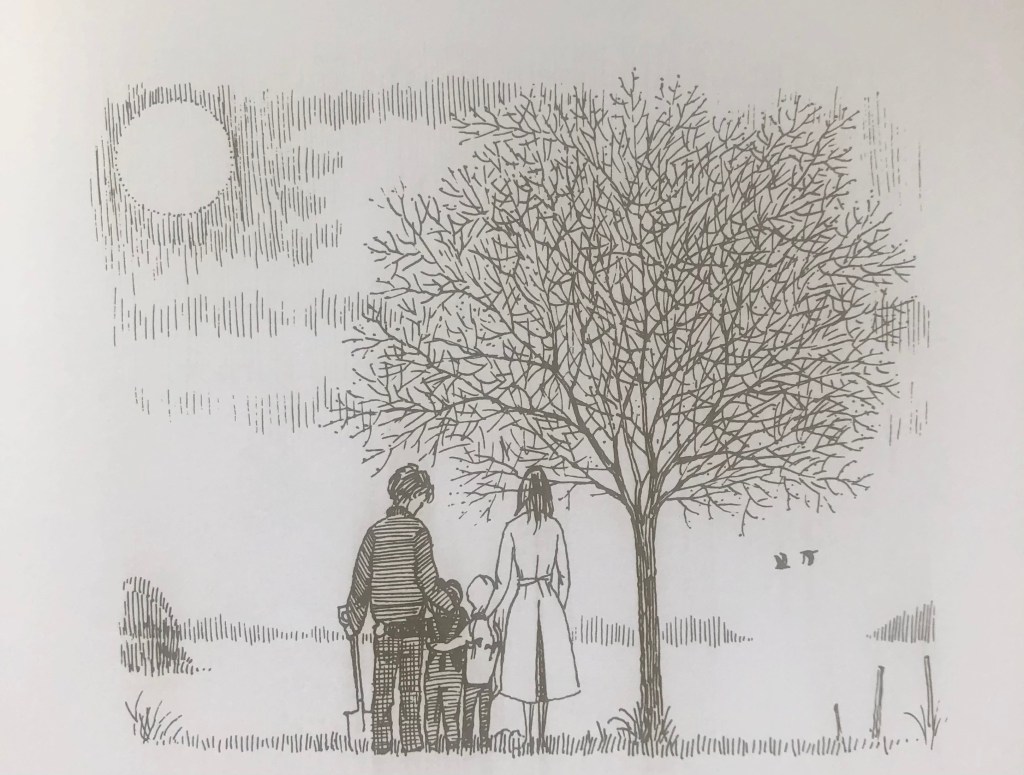

Compare the two images here: the little bird from The Bear and the Wildcat and the family saying goodbye to their cat in Viorst and Blegvad’s The Tenth Good Thing About Barney. Both sparse in their own way, but the impact of the image in Barney is more muted because of the lack of the cat. Because Barney is really about the burial and what happens afterwards, Erik Blegvad focuses on the family (and the argument about heaven and decomposition). This is not an easy text, but it is the ideas in the dialogue that stand out for me.

A number of writers discuss death in picturebooks. Kelly Swain, for example, in the Lancet Child and Adolescent Health writes of her neice asking rather literally whether Great-Grandma Nancy had gone up to heaven or into the ground. The same question occurs in Barney. In the debtae about whether the cat is in heaven there is real impatience and ambiguity. Not so for the little bird in The Bear and the Wildcat, whose dead body is shown starkly but without sensation: the focus here is grief.

We meet bereavment in Varley’s classic (and in its time quite daring) Badger’s Parting Gifts, and we have also a desctription of death from Badger’s point of view: a “strange yet wonderful dream” yet going down a tunnel (a sort of good place for a Badger to go, and actually not unlike the behaviour of some Badgers).

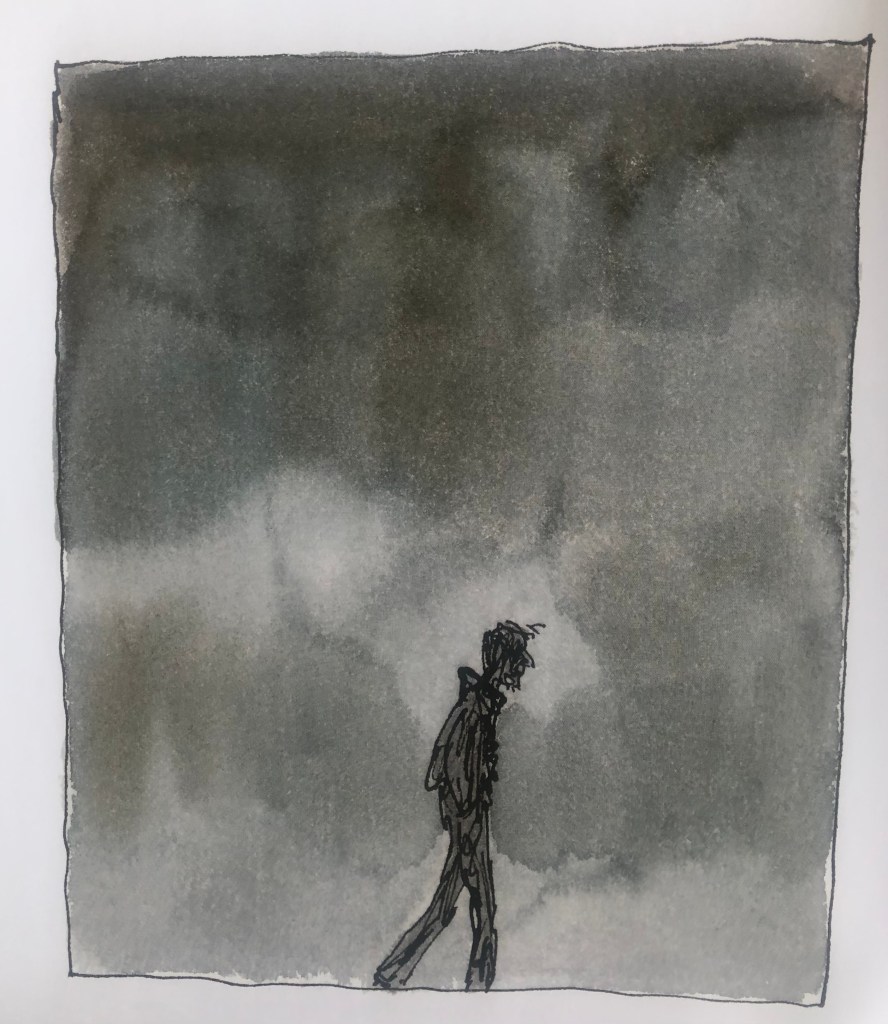

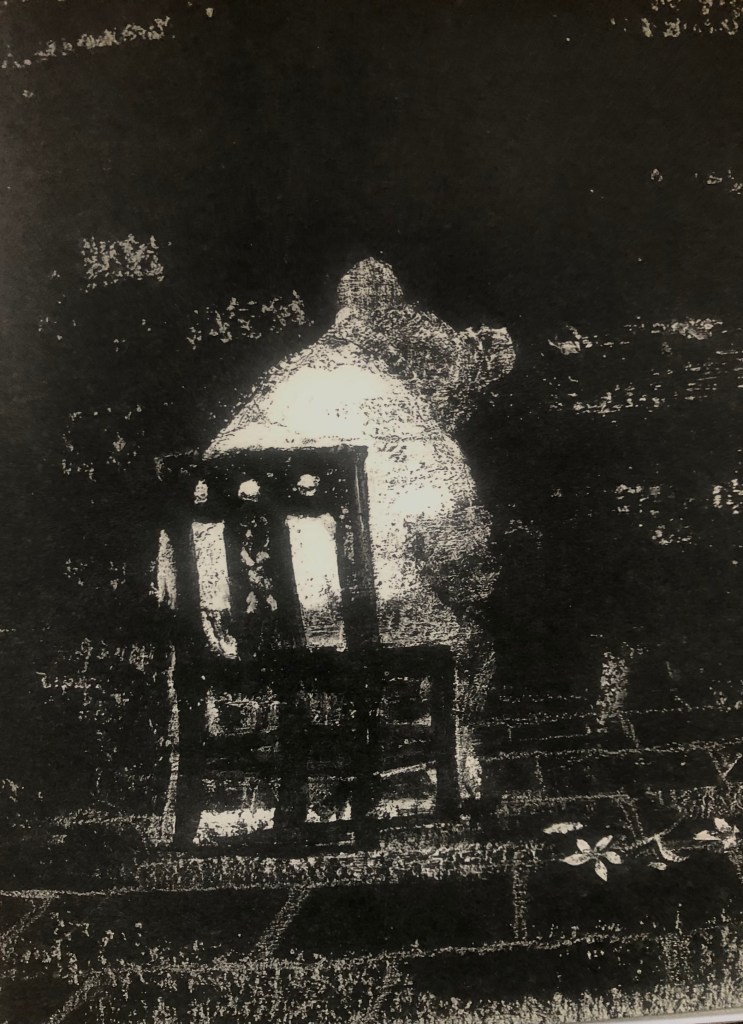

The book that still feels to me raw and angry as well as deeply felt is the great book by Michael Rosen, his Sad Book, where Quentin Blake’s artwork walks hand-in-hand with Rosen’s pain.The lone figure in the evening rain, hands in pockets; the single candle of a painful solitude. In many ways the turning-point picture in The Bear and the Wildcat seems to me to be much the same: despairing loneliness, and the overarching bleak dark. Painful to read, but beautifully told, and certainly chimes with my own experience. In discussing the Sad Book Maria Popova in the gobsmacking Marginalian blog puts it so well:

What emerges is a breathtaking bow before the central paradox of the human experience — the awareness that the heart’s enormous capacity for love is matched with an equal capacity for pain, and yet we love anyway and somehow find fragments of that love even amid the ruins of loss.

Michael Rosen’s Sad Book: A Beautiful Anatomy of Loss, Illustrated by Quentin Blake https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/08/25/michael-rosens-sad-book-quentin-blake/

Other stories are possible, too. In Maia and What Matters we have a true-to-life complicated story of a grandmother losing her words and mobility, a grandfather dying, and little Maia, caught by all sorts of adult pressures being the one who knows what matters. True-to-life text here stands in tension with dreamy artwork where symbol and tone show Maia growing and loving and getting angry and taking charge in page after page of real days and might-have-beens until we are at the final denouement of grandma beside her husband’s coffin, stroking his hair. (As an aside I decided only to show the cover, because the large format of the book would be given no recognition by a small picture or excerpt of a larger spread)…

I have mentioned the companionship of death in Duck, Death and the Tulip – like The Bear and the Wildcat, another triumph from Gecko Press – and the picture here shows tenderness – and comedy? The incongruity of their friendship [until a cool wind ruffles Duck’s feathers] does allow for a wry smile:

Actually he was nice (if you forgot for a moment who he was). Really quite nice.

Wolf Ehrbruch, Duck, Death and the Tulip.

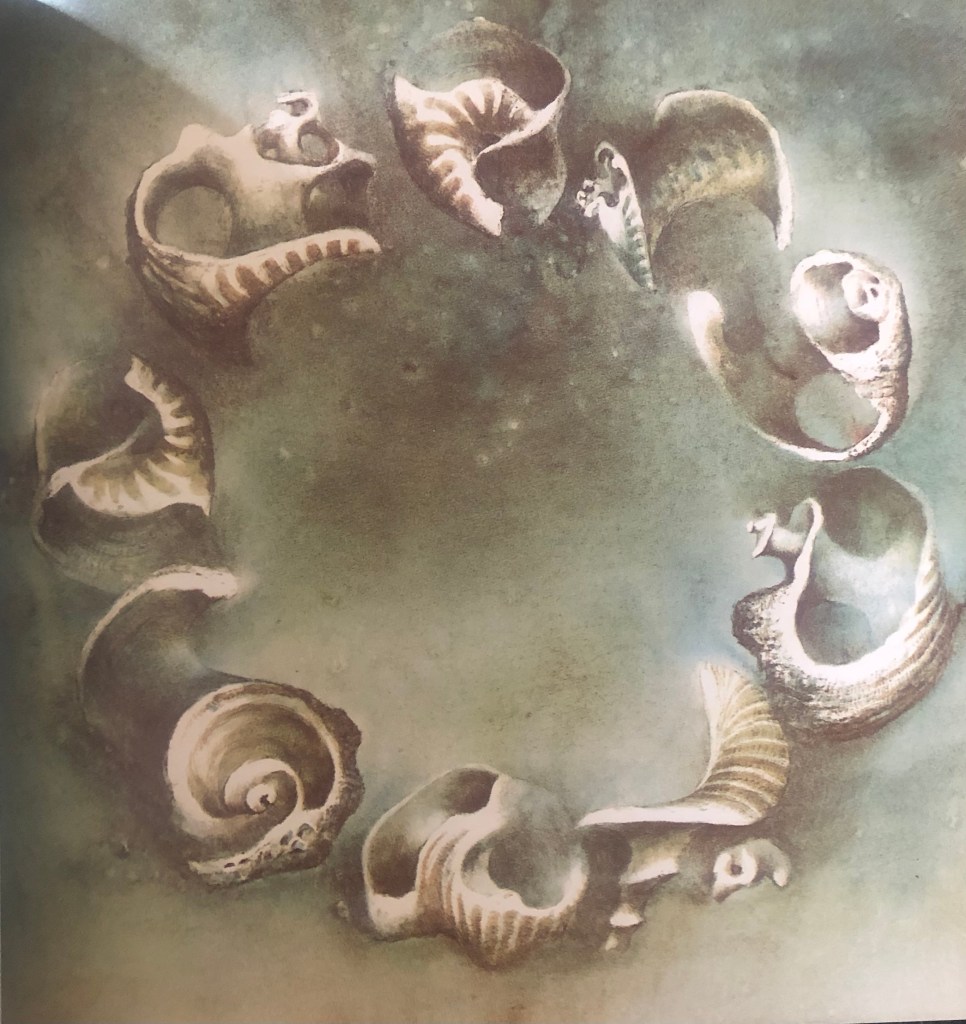

In The Bear and the Wildcat we look hard at grief; but in Thomas and Egneus’s Fox: a Circle of Life Story it is remarkable in its absence. The vixen is hit by a car, the cubs watch and then go their way. The fox is part of the autmnal decay –

Back to earth, to plants, to air flow the tiny particles that were once a fox.

Isabel Thomas, Daniel Egneus Fox: A Circle of Life Story

And so we come to a couple of books that do not look at grief, or at the possibility of an afterlife, but at a stark reality – only to find that in neither book is it particulartly harsh. The fox dies (quickly: no agony; no hunting horn) and in this last text, Lifetimes by Bryan Mellone and Robert Ingpen,

Nothing that is alive goes on living for ever… Sometimes, living things become ill or they get hurt. Mostly, of course, they get better again but there are times when they are so badly hurt or they are so ill that they die because they can no longer stay alive.

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/113067/lifetimes-by-bryan-mellonie/

I might raise an eyebrow at the over-comfortable “Mostly,” but the book is clear about what will happen, and that this is part of they way things live “and that is their lifetime.”

So there seem to me to be ideas here worth disentangling. I have had to cut out for brevity Oliver Jeffers’ wonder The Heart and the Bottle in which grief is the key driver of the narrative – or, if not grief, then the love that engenders sorrow – and Glenn Ringtved’s Cry, Heart, But Never Break where again a personification of death imparts some wisdom, and so many more. But these stories deal with two principal themes: bereavement, and inevitablity/natural cycles. Maybe the “inevitability” books are ones that any child will be intrigued by; the bereavement books may have a particular audience. And this was where I stumbled in my review for Just Imagine. When asked “Who is this book (in this case, The Bear and the Wildcat) for?” it is often hard to pick an age range or educational context. Does this mean, however, that we must restrict children’s reading? Not for me: but it does mean that it is incumbent on educators (including the wonder that is a good school librarian) and parents to approach books with respect and something like humility. There are books for children and among them ones that will move adults to tears as well, and sometimes, even in the heart of their own sad time, the grown up needs to see which book a child might like, be interested in, be comforted by. It’s not easy.

I have met educators and parents who have said, of Duck, Death and the Tulip, that they would “never let a child have that book.” It clearly stirs something in us of a desire to protect children from the ultimate monster under the bed; yet there is even in that book a sense of hope. Death is not something to fear. And in the book that sparked this blog post, the sensitive and beautiful story of a bear who has lost his best friend, there is hope. Not some great afterlife hope – even though we are in Easter Week as I write – but simply that friendship helps, and that life goes on. |It can be painful and crazy as in Sad Book, and it can look like the comfort is illusory as in the discussions around Barney the cat, but there is this: compassion and friendship.