I need to preface what I am going to write here by saying that I know that adults read for themselves or for children for a wide, wide range of reasons, and that the key reason why many of us are involved in children’s literature is at its heart pedagogic: we read because we want our students to appreciate our passion, whether they are three in nursery or thirteen in secondary school or training to be teachers or established teachers exploring at postgraduate level. I therefore do understand why teachers ask “Is this suitable for Y2s?” and “Could I use this with the Y7s?” It’s just that this is not where this blog post is starting from.

If we think about literature at any level – let’s say a hard-but-marvellous book like Tristram Shandy, or the much-loved Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam – we are confronted by questions like

- Do I understand this?

- Does it teach me anything?

- Does it give me pleasure?

before (or alongside the moment where) we move into questions such as

- What does this text tell us about the historical context of its composition?

- How does the author use language to convey character?

- Does the narrative structure (or lack of it) illuminate something about the writer’s ideas?

It is true, it seems to me, that the thoughtful reader moves beyond what Bachelard calls “sentimental resonances” produced by text or image. It may be that what Chambers (and others, standing on the shoulders of giants) suggests about developing a community of readers is partly about moving beyond the simple pleasure to the more analytical or critical joys of exploring text and design and language and… and… I find myself getting lost, or maybe I just get the feeling it would be good to come to something of a critical approach, the single, sharp insight on what Children’s Literature is and does, a spearhead.

When I look (as I often have done; as I am doing this evening) at Rob Pope’s English Studies Book, I wonder where Children’s Lit fits into the complexity of English Studies. Are we looking at close reading, with the text-centredness also taking into account the hand-in-hand nature of image and text in picturebooks where it might need to? Are we, as critics and consumers, reading a culture and doing so by consuming a cultural product/object? Do my gender/sexuality, ethnicity, culture come into play? Just as Pope suggests “No-one has a single, pure and fixed position.”

And here we are at the nub of the issue. Not only do we as critics not have a single apparatus to wheel in to view Children’s Literature, it may be that we cannot view Children’s Literature , in all its complexity, as a unified subject for discussion. Can we really look at The Secret Garden as part of the same phenomenon as Revolting Rhymes simply because they are both accessible to Primary-aged children? We might follow Tolkien though his themes such as Escape and Fantasy and see recurrent themes, but how much are these really uniting Elphinstone’s Sky Song with the Rosen/Oxenbury Bear Hunt or The Children of Green Knowe with My Father’s Arms are a Boat? Am I trying to make a unified subect because working with children by sharing books (or working with people who will work with children sharing books) is somehow more straightforward than facing complexity?

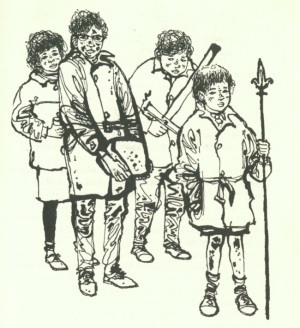

Let me come back to spearhead as an interesting image. It reminds me (for some reason) of the spear hefted by Roland, one of the children in Elidor (Jake Hayes’ blog is a beaut) – and that took me further, to Charles Keeping’s image of the weary children – and that took me in turn to the four gifts the children have entrusted to them: spear, sword, cauldron and stone. While I’m not suggesting that Garner has consciously presented here an allegory of lit crit, it does strike me that these four treasures (in all their C20th grubbiness) can be asked to stand for the notion that we need more than one thing to preserve the magic, to allow for the critical-but-not-dismissive/destructive eye. The close reading of one reader; the eye to sources and history from another; the pedagogic “Can I use this for my science project?” or”we’re doing fairy tales, where should I start?” or “where is the vocab I need to teach?” of others. Maybe we need them all, the field is so diverse.

Adults and children read for a wide, wide range of reasons; we enter not a single section of a bookshop, but a richly unfolding section upon section of fantasy, pathos, travel, speculation, high adventure and myth. We call it Children’s Literature when really it might at least have a plural. “What are your researching, Nick?” “Oh, Children’s Literatures.”

And now I have lots more to think about.

*

Bachelard, G (1958, translation 1964) The Poetics of Space, trans Maria Jolas. New York: Penguin USA

(I am indebted to Nikki Gamble for discussing Bachelard on Twitter and moving me to explore his work)

Chambers, A (nd) Booktalk http://www.aidanchambers.co.uk/booktalk.htm and The Reading Environment http://www.aidanchambers.co.uk/readingenviro.htm accessed 29.10.18

Halford, D and Zaghini, E (2004) Folk and Fairy Tales: a Book Guide. London: Booktrust

Lesnik-Oberstein, K (1994) Children’s Literature: Criticism and the Fictional Child. Oxford: OUP

Pope, R (1998) The English Studies Book. London: Routledge

Tolkien, J (1964) Tree and Leaf. London: George Allen and Unwin

One thought on “Using Children’s Literature”